Lass uns die Welt vergessen- Volksoper 1938

Vienna Volksoper’s Let us forget the world -on Volksoper’s 125th anniversary- pays tribute to the 1938 cast members. After the Anschluss– Austria’s incorporation into the German Reich- many of Volksoper’s cast, Jewish, lost their jobs, and later their lives, in concentration camps. ( Austrian and German musical theatre in the 1920s and 30s was dominated by Jewish stars, composers from Kalman to Korngold. Franz Lehar- Merry Widow, a world hit, beloved in Nazi Germany- was persuaded to stay, in spite of his Jewish wife. But numerous scriptwriters, librettists, and musical talent emigrated to the US.) In Lass uns die Welt vergessen, today’s 2023/4 cast identify with members of the 1938 Company, reliving their stories. Score and performance- researched by Volksoper’s conductor Keren Kagarlitsky – sound stunningly authentic.

A montage of black/white newsreel footage of Vienna in 1938; foreboding music (snippets of Schoenberg, Mahler) : the historical context to Austria’s merging with Germany, the Anschluss, (including Hitler’s thanks to the Austrian people.)

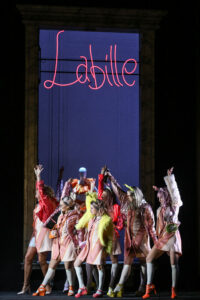

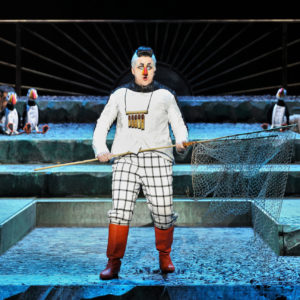

At Volksoper, they’re actually rehearsing ‘Gruss und Kuss aus der Wachau‘, a 1938 hit by the success team of Benes, Wiener, and Breuer, Löhner-Beda, directed by Hesky (Jacob Semotan.) ‘We can’t go on as if nothing’s happening; ‘stick our head in the sand’ (Löhner-Beda). ‘I’m putting on theatre. No politics!’ insists Hesky. He’s fighting a losing battle to put on the show. While they’re rehearsing – ‘another four cast gone?’ More Nazi persecution of political dissidents and Jews. Then cut to a brightly-lit stage, candy floss colours, showing three girls on a production line in a tobacco factory. ‘We don’t want to stay single any longer’, they breezily sing.

Theu Boermans’ production constantly intercuts between the bubbly, over-the-top musical numbers being rehearsed: the encroaching political reality of Nazi interference, political purging; and the private lives of Volksoper’s (1938) writers, actors, musicians, and conductor, (roles played by 30 of Volksoper’s 2024 cast.) As many were Jewish, their dilemma is whether to put up, or pack up.

Joanna Arrouas plays Hulda Gerin, (later famous as mezzo Hilde Guden); but from 1938, black-listed by Nazi race laws – in spite of her Nazi-connected father- through her Jewish mother.

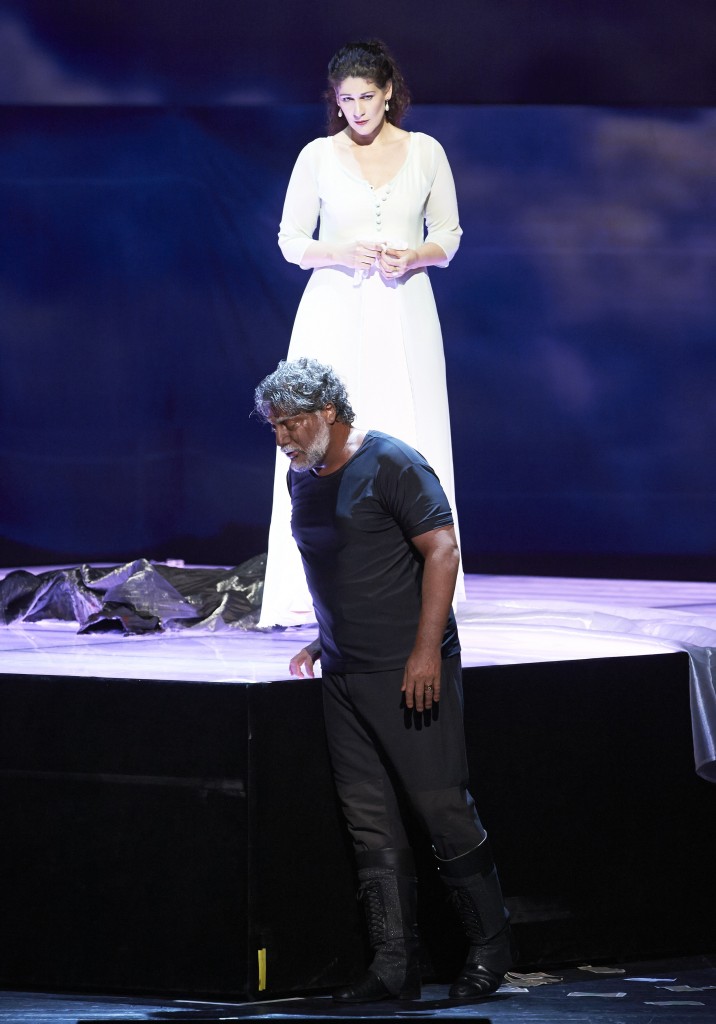

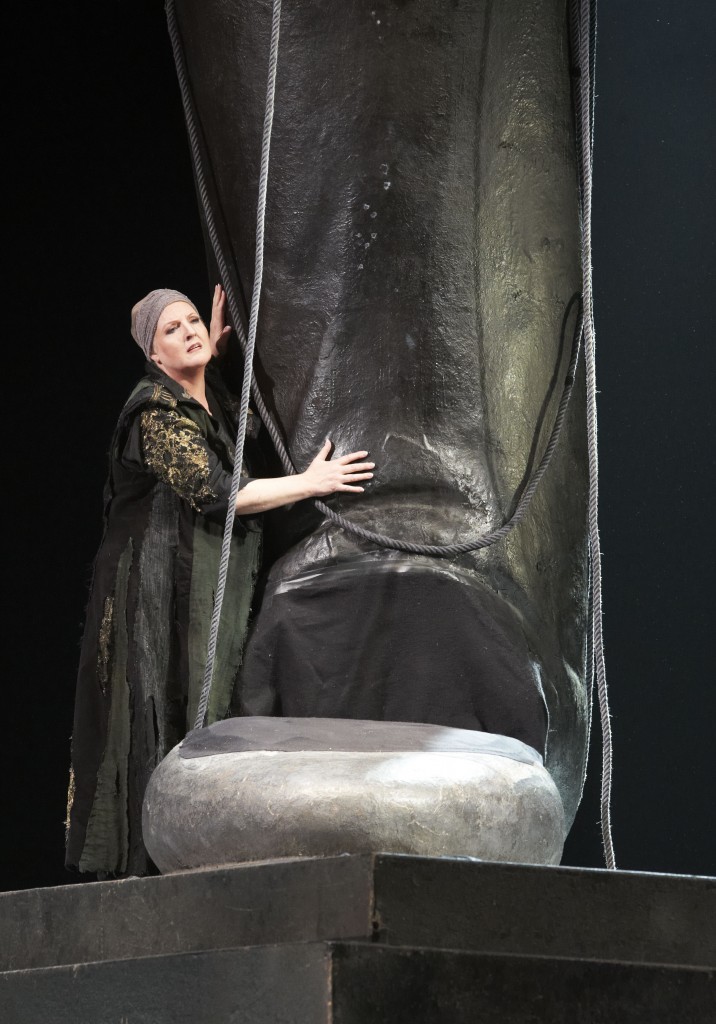

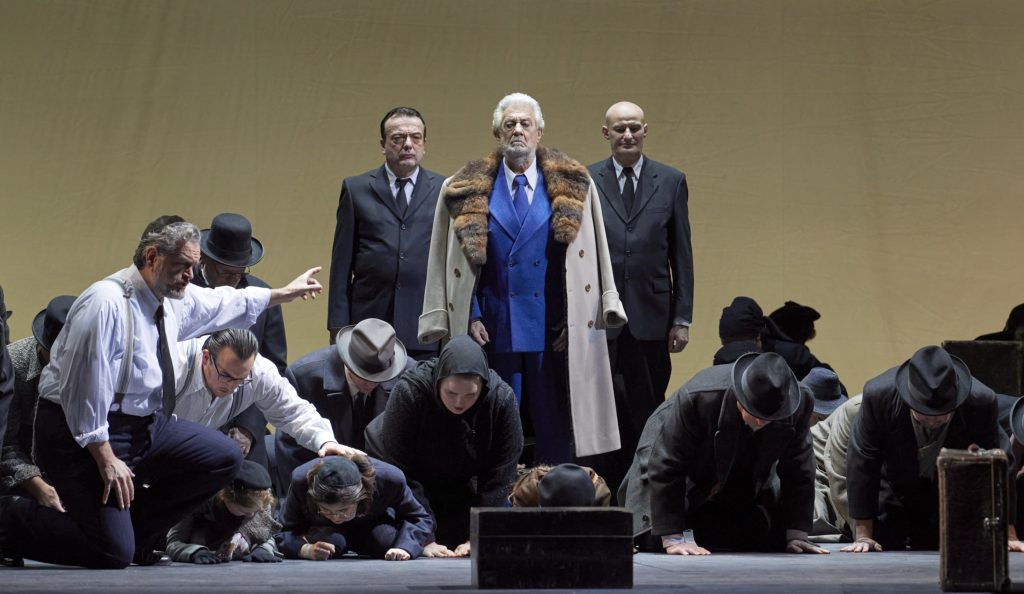

On a circular stage ( Bernhard Hammer), an open-plan house on different levels represents Vienna’s Jewish community, anxiously debating their fate. The opening full house, of Jews on different levels, empties, shrinks to a scaffold; until finally there’s only Beda, Carsten Süss ( in convict’s pajamas), on piano, composing from Buchenwald.

By contrast , a comic middle-aged couple in idyllic country setting- picnicking- singing of Dummheit , stupidity. ‘Manchmal, sometimes , I can’t believe a hero lurks within me!’

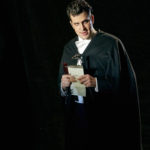

The Jewish conductor Herbert Adler (Lucas Watzl) makes a stand. ‘If we continue we’re collaborators; the orchestra will tolerate him’, he hopes. A soldier in Nazi uniform walks on. They eventually dominate the stage, symbolizing the (political) take over. But ‘the world needs music, even when it’s cowardice’, is the argument for carrying on.

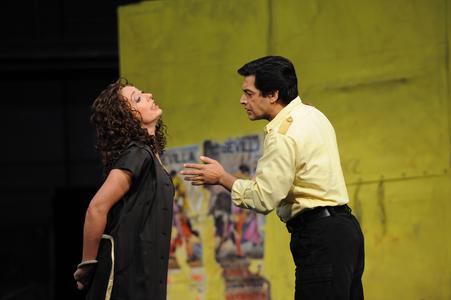

A café scene, light, apple-green, checked table cloths. The lovers, the chauffeur (Ben Connor), and ‘Miss Lilac’ (Arrouas); it’s love at first sight, never felt this way, they sing . Then the ensemble, ‘ Give me a sexy kiss’, to light-hearted tuba and brass accompaniment. It builds to a colourful rustic dance scene, the choreography (Hurler), split-second professional, and it’s only in early rehearsal! Gerin sings, she didn’t want to be in the cast… Then, something’s happening back of the the stage

They all stand to attention. To the Fuhrer’s speech, the announcement of the Anschluss on the big screen: newsreel of the celebrations . Huge crowds cheering. (Chilling.)

Meaning the implementation of the Race Laws, and Jews persecuted. Jews are seen (on archived film), on their knees cleaning the streets, and sidewalks . Back to ‘the Jewish house’, and its different rooms and stories. “It’s time, I’m going to Bogota.” – ‘Victor (Flemming) has fled.’- ‘That coward!’ We hear their gossip. Kurt Adler escaped to Chicago , (from 1953, Director of San Francisco Opera.) ‘I can conduct anywhere, ‘ -we overhear- in New York , or London.

The storm troopers are inside, on stage, broken into the Volksoper building. More documentary film- “Austria decides voluntarily through a Referendum.” – ‘Why are they returning this idiot as their savior,’ we hear off-stage. Yet (in the ‘Forget the world’ argument, ) ‘theatre is the one thing that can save the nation.’

But in the grim political reality…Their conductor, Löhner-Beda, (Carsten Süss), must be removed from the Volksoper. ‘Be vigilant of the Jews‘, the SS officer intones. There is a demand for the resignation of all Jews in the Company. The Director Hesky (Semotan) tries to leave, but is countermanded: refused until the production is over.

While in another world- shifting to the world of operetta- we’re in a lush green, glossy landscape. ‘The world is like a garden. It’s so beautiful here /Join our cheer’, Volksoper Chorus sing, the irony hinted at by the trombone interjections, (like farts.)

‘You’re famous in Austria and Germany’. Left of stage, an interrogation area, a singer seated with an SS officer. ‘We have a special camp’, (he explains)- Theresienstadt, in Nazi propaganda, a ‘holiday camp’ for artists.

‘We walk hand in hand in meadows’, sing the Chorus, in an exuberant musical episode, like a travelogue. The counterpoint to these lilting, euphoric waltzes. Now horror as the beautiful, radiant folk dancers in their multicolored dresses are dancing partnered with Nazis in brown uniforms.

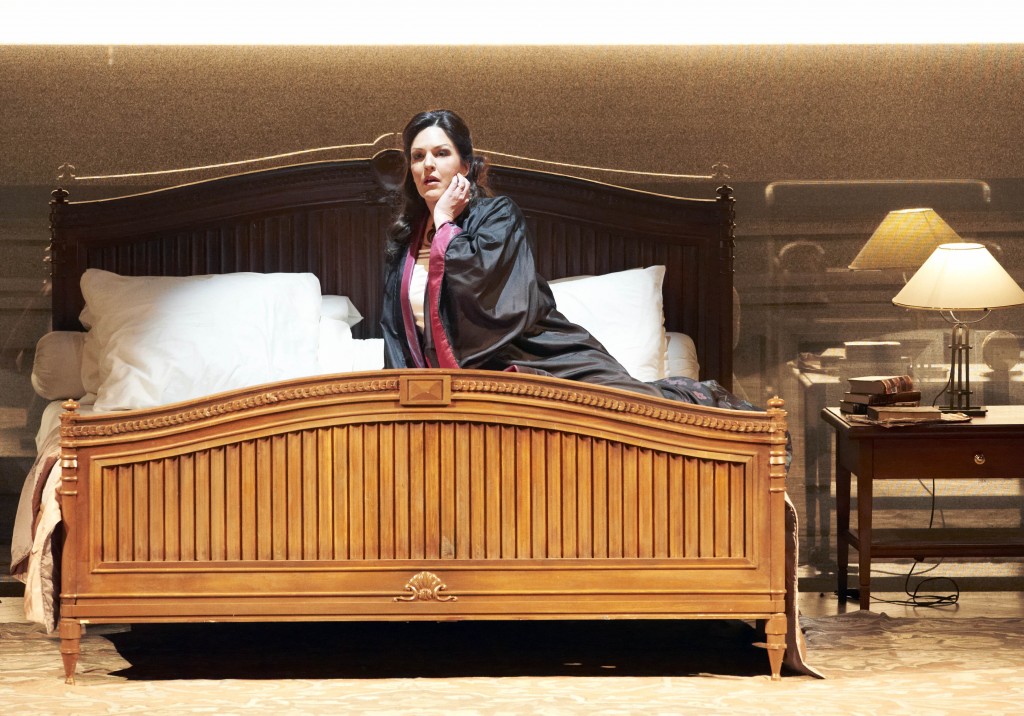

Yet we cut to the glamorously dressed Hulda Gerin in a lilac silk dress . Oh, golden age of chivalry full of splendour! sings Arrouas, who (ironically) has married into aristocracy. Now she’s the Countess Kürenberg. (What happened to her chauffeur?)

The Pflicht , the legal duty of Nazis, is the alienation and expulsion of Jews, Jews stripped of any legal rights.– Mrs. Gerin is excused.- ‘So you really are…Jewish?‘ they exclaim. But angrily Arrouas pulls off her evening gown, stripped down to her negligee. ‘You’ll have to find somebody else’, she retorts.

A flurry of doll-like, peroxide blondes offer to fill her place. A frivolous example of how Jews , and political undesirables were expunged, ‘cancelled’, and replaced by ‘pure’ Arian types.

To the left-of-stage, the SS interrogations go on . -‘Driven out, stateless’, one Jew comments, ‘the English didn’t want us. We’re German Jews!’

We glimpse Löhner-Beda (Casten Süss) wearing convicts’ stripes , who sings, ironically, ‘Oh Buchenwald we can’t forget you.’

But in the slickly-timed direction, and Hurler’s choreography, the black-clad widows in a line up, are transformed into Can-Can dancers. Sensational! Their black silk dresses uplifted revealing white frilly crinoline lace. Kicking their legs in very professional style.

Hesky (Semotan), in his signature camel great coat, comes back, stooped, defeated; pissed, he’s accompanied by high-ranking SS officers, in navy tunics with red-beading. Semotan’s is a powerful, moving, performance, one of many.

Now Volksoper’s Intendant walks off , as three SS men get drunk . And the new Intendant wears a Nazi armband. After the Anschluss purges, it’s announced, only Arian German music will be played.

The stage is now taken over by five Nazi weddings. The music is militaristic, goose-stepping brass -trombones, tuba predominate. ‘All our love and kisses from Wachau! ‘, (they sing as if naively.)

There’s a sobering post-script. A roll call/ obituary of each of the 1938 Volksoper cast. Löhner-Beda died in Auschwitz, also Viktor Flemming, amongst others, and in other concentration camps.

On the empty stage , the sweeper, a linkman, the ‘common man’, laconically addresses the audience. – ‘What else to say…We’re closing.‘

I cannot remember when a Volksoper audience last gave a unanimous standing ovation. Only four performances, and I nearly missed this historic theatre-making. © PR. 5. 1. 2024

Photos: Theresa Dax , Ben Connor ; Carsten Süss, Marco Di Sapia, Lucas Watzl, Johanna Arrouas, Jacob Semotan © Barbara Pálffy/ Volksoper Wien

![51668_Les_Martyrs_1__c__Werner_Kmetitsch[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/51668_Les_Martyrs_1__c__Werner_Kmetitsch1-150x150.jpg)

![06_Aida_121736_PIAZZOLA[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/06_Aida_121736_PIAZZOLA1-150x150.jpg)

![Manon_Lescaut_90969_NETREBKO_GIORDANI[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Manon_Lescaut_90969_NETREBKO_GIORDANI11-e1472558974376-1024x976.jpg)

![Manon_Lescaut_90948_BANKL_PERSHALL[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Manon_Lescaut_90948_BANKL_PERSHALL1-150x150.jpg)

![Manon_Lescaut_90939_NETREBKO[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Manon_Lescaut_90939_NETREBKO1-e1472559314489-271x300.jpg)

![Manon_Lescaut_90951_GIORDANI_NETREBKO[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Manon_Lescaut_90951_GIORDANI_NETREBKO11-150x150.jpg)

![Boris_Godunow_90434_PAPE[1] 2](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Boris_Godunow_90434_PAPE11-e1469877999353-1020x1024.jpg)

![Boris_Godunow_90477_RYDL[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Boris_Godunow_90477_RYDL1-150x150.jpg)

![Boris_Godunow_90475_GARIFULLINA_PAPE[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Boris_Godunow_90475_GARIFULLINA_PAPE1-150x150.jpg)

![Boris_Godunow_90476_ERNST[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Boris_Godunow_90476_ERNST1-150x150.jpg)

![Lohengrin_90507_VOGT_NYLUND[1] C](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Lohengrin_90507_VOGT_NYLUND1-e1467376686536-1024x958.jpg)

![Lohengrin_90501_SCHUSTER[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Lohengrin_90501_SCHUSTER1-150x150.jpg)

![Lohengrin_90514_VOGT_NYLUND[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Lohengrin_90514_VOGT_NYLUND1-e1467377257689-150x150.jpg)

![07_Tri_Sestri_88252_KHAYRULLOVA_GRITSKOVA_GARIFULLINA[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/07_Tri_Sestri_88252_KHAYRULLOVA_GRITSKOVA_GARIFULLINA1-e1461415055737-1024x838.jpg)

![05_Tri_Sestri_88311_GRITSKOVA[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/05_Tri_Sestri_88311_GRITSKOVA11-e1461582313515-150x150.jpg)

![Cardillac_80190_BEZSMERTNA_KLINK[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Cardillac_80190_BEZSMERTNA_KLINK1-e1438687375107-959x1024.jpg)

![Cardillac_80188_KONIECZNY[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Cardillac_80188_KONIECZNY11-e1438687641948-300x231.jpg)

![Nabucco_45563_BOHINEC_PERTUSI[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Nabucco_45563_BOHINEC_PERTUSI1-e1435238431741-1024x994.jpg)

![Nabucco_54619_LUCIC[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Nabucco_54619_LUCIC1-e1435237924217-150x150.jpg)

](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Nabucco_78625_GULEGHINA11-150x150.jpg)

![02_Siegfried_51376_STEMME[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/02_Siegfried_51376_STEMME11-e1411041306417-150x150.jpg)