Nicolas Joel’s spectacular production of Verdi’s Aida has been wowing audiences at Vienna State Opera since 1984. The monumentally extravagant sets are probably no longer affordable at a time of cuts; and historically authentic reproductions, now unfashionable, replaced by minimalism. So this revival is a rare treat. But the opera isn’t just about spectacle, although commissioned and premiered in Cairo (1871). Verdi’s genius was to use the set of Aida to juxtapose intimate moments against vast crowd scenes : the protagonists’ loves are in conflict with their public duty.

Nicolas Joel’s spectacular production of Verdi’s Aida has been wowing audiences at Vienna State Opera since 1984. The monumentally extravagant sets are probably no longer affordable at a time of cuts; and historically authentic reproductions, now unfashionable, replaced by minimalism. So this revival is a rare treat. But the opera isn’t just about spectacle, although commissioned and premiered in Cairo (1871). Verdi’s genius was to use the set of Aida to juxtapose intimate moments against vast crowd scenes : the protagonists’ loves are in conflict with their public duty.

So the opera begins (and ends) with pianissimo music, Act 1 beginning with Radames famous aria thus forgrounding the love interest. The army Captain Radames is at the centre of a love triangle: loved by both Amneris, King’s daughter, and the slave Aida. And like a Shakesperean tragic hero – Othello, Macbeth are also Verdi operas – a valiant man is dissipated, brought down by a fatal weakness. Radames cannot help loving Aida, who will be his downfall. Radames, in his opening aria, dreams of honour, and fame, and of Aida. Jorge de Leon, to a cello accompaniment, sings splendidly of the heavenly Aida, how he wishes to bring her to the blue skies of her native land. Ramades is a role demanding constant changes between the dramatic and lyrical (right up to the death scene): a tremendous vocal spectrum. De Leon hits thrilling high notes.

So the opera begins (and ends) with pianissimo music, Act 1 beginning with Radames famous aria thus forgrounding the love interest. The army Captain Radames is at the centre of a love triangle: loved by both Amneris, King’s daughter, and the slave Aida. And like a Shakesperean tragic hero – Othello, Macbeth are also Verdi operas – a valiant man is dissipated, brought down by a fatal weakness. Radames cannot help loving Aida, who will be his downfall. Radames, in his opening aria, dreams of honour, and fame, and of Aida. Jorge de Leon, to a cello accompaniment, sings splendidly of the heavenly Aida, how he wishes to bring her to the blue skies of her native land. Ramades is a role demanding constant changes between the dramatic and lyrical (right up to the death scene): a tremendous vocal spectrum. De Leon hits thrilling high notes.

Amneris, (Olga Borodina, a very impressive mezzo), madly in love with Ramades, sings of rare joy: enviable the woman who can kindle such passion. She hears of his dream to be Commander: but was the dream not of something else ? She intuits, someone; her suspicions aroused when Ramades sees Aida. The trio (Aida, Amneris, Radames) immediately forefronts the love triangle. Amneris is seen with Aida (Kristin Lewis) , who’s always treated her as a sister rather than a slave.

Radames wants to know why Aida is crying: she’s ‘heard the cries of war’. But Aida’s tears give her away. She weeps for her beloved country. Now the spectacular entrance of the soldiers. The King (Janusz Monarcha) announces Egypt is invaded by the Ethiopians. The Chorus sing, ‘Let war and death be our battle cry!’; and celebrate Radames as Commander. Magnificent crowd scenes; Vienna State Opera chorus always excel in Verdi.

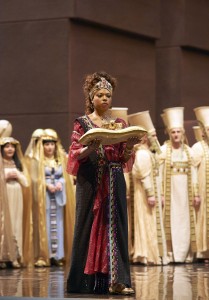

Aida, however, alone- in her key aria,’For whom do I weep’- sings of her dilemma. She is in the country of the foreigner. Her Radames is about to fight against her own people led by her father Amonasro. Kristin Lewis is short, dark- skinned , wearing a red and gold outfit, her ‘afro’ hair crowned by a gold head piece. Then, on her knees, she wishes Ramades death: yet loves him. What anguish; she cannot speak the words ‘father’ or ‘lover’. Kristin Lewis is truly moving -inspired casting. But then Lewis has sung the role of Aida internationally countless times: although her first time in Vienna, now her home. And, first night, she earned a tremendous ovation.

Act 2 ,featuring the confrontation between Amneris and Aida, opens to a sensational set – gold-headed maidens like swans, with Amneris being dressed to celebrate the Egyptians’ victory. Olga Borodina has considerable presence, and in her aria ‘My love come and intoxicate me; make me happy’ longingly anticipates Radames. But she’s tormented by uncertainty: must know if Aida is her rival. She will unlock her secret. In their duet, Amneris empathises with Aida’s grief: offers Aida, far from home, everything to make her happy. ‘Tell me your secret: is there a brave warrior amongst your defeated people?’ Then, the bombshell: ‘Radames was killed by your people’…’You love him. Look at me!’

Lewis’ Aida is now centre stage.’You keep lying! You love him ! The daughter of the Pharoahs is your rival’. Then Amneris (Borodina) retracts, has pity for Aida – wretched, let your heart break.’This love will be your death.’ Amneris will be celebrating on the victory march: she, Aida, will lie in the dust. Aida, alone, pleads, ‘Oh gods have pity on my sufferings’- Lewis outstanding.

But in the victory march (Act 2, scene 1), the Chorus (and such a chorus!) sing ‘Glory to Egypt and Isis, and to the King, all in gold, carried on high by bearers. The fabulous spectacle is truly breathtaking; but this is the public show. The heart of the opera is in the love-torn protagonists. A ballet is performed centre stage -the women made up in gold, virtually nude, the men, black-skinned, in gold and black outfits, gold headgear- the Egyptian Court side stage.

So ‘Come brave warrior!’ Radames, offered a wreath of victory, is saluted by the King as Egypt’s saviour. The King ‘will grant him any wish’. But which, ironically, Ramades cannot reveal: his secret, Aida, the slave girl. Ramades requests the prisoners be brought before them.

In a key scene – a characteristic Verdian moment – Aida sees her father , King Amonasro, (white-haired Markus Marquardt),who begs her not to betray him.  Amonasro, concealing his identity, pleads the King’s clemency for the Ethiopian captives. ‘Today this is our fate : tomorrow it might be yours’- Verdi’s (often repeated) humane message. The Chorus of soldiers demands ‘destroy them’ -singing in counterpoint to the slaves, centre stage, pleading leniency. Radames asks for the freedom of the prisoners; only Aida and her father remain as hostages.

Amonasro, concealing his identity, pleads the King’s clemency for the Ethiopian captives. ‘Today this is our fate : tomorrow it might be yours’- Verdi’s (often repeated) humane message. The Chorus of soldiers demands ‘destroy them’ -singing in counterpoint to the slaves, centre stage, pleading leniency. Radames asks for the freedom of the prisoners; only Aida and her father remain as hostages.

And now, to the jubilation of the crowds, the King offers Ramades his daughter in marriage. Both the crowd’s and Amneris raised hopes are bitterly ironic, given the private truth.

Fathers and daughters divided between patriarchal loyalty and opposing lovers. A Verdian theme. The King- prior to Amneris’ marriage to Radames- tells her Isis reads into the heart of mortals: their secret wishes. Amneris- wonderfully sung by Borodina- prays Radames will love her with all his heart. Meanwhile, Lewis’s Aida, shrouded in black, awaits Radames. Her aria, to an oboe introduction, laments ‘O fatherland, I shall never see you again’-a familiar motif in Verdi- the skies and breezes of the land of her youth. Lewis reaches powerful high notes. Her father, Amonasro will prise her from her lover- reminding her of her loyalty to him and her country. Father, have pity, she pleads.’You call yourself my daughter! The dead will curse you.’ What a price for her to pay.

When at last reunited with Radames Aida is ambivalent. She reminds him he’s bethrothed to another, of his vow. Is he not afraid of Amneris’ power? Then, let them flee. Aida asks him to go to a foreign land.- But how can he forget his fatherland, the country where he won fame?- Now she taunts him, he doesn’t love her, unless he’s prepared for exile. He accepts: they’ll be united in her fatherland.

Amonasro has been listening in. She’s betrayed Radames. Amonasro offers him a throne, but Radames realises he’s betrayed his country. The trio is powerfully rendered. Radames gives himself up to the guards, for revealing the Egyptians’ plans.

Thus the tragic hero has sunk to his nemesis.’Traitors must die!’. Yet Amneris, in her aria, still loves him ; if he loved her she would save him. But Radames would rather die than never see Aida again. ‘For her, I betrayed my fatherland and honour’– de Leon powerful, with terrific delivery on high notes- ‘May Aida know I died for her’. He has no fear of his people’s anger: he’s lost. Amneris, in her aria, blames herself, desperately pleads Radames’ innocence. In counterpoint the Choir chant, he betrayed his fatherland.

In the finale- Aida secreted into Radames’ tomb- Aida /Radames duet attests to the self-delusion of love. She’s too lovely to die. (The angel of death will open heaven..) They’re buried alive, but intoxicated in their passion. They’re defiant, staring out (of their stone bunker).The opera ends as it began with pianissimo strings; private happiness sacrificed to war. Vienna State Opera orchestra and choir, conducted authoratively by veteran Pinchas Steinberg, justified a fine cast. And those sets! PR 12.03.2013

Photos: Kristin Lewis (Aida); Jorge de Leon (Radames); Olga Borodina (Amneris); Janusch Monarcha (King); Kristin Lewis and Markus Marquardt (Amonasro)

(c) Wiener Staatsoper/ Michael Pöhn

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog