Richard Strauss’s (1909) opera Elektra was his first collaboration with librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Recreating the ancient Greek myth, the opera is modernist in its focus on Elektra and her mother Clytaemnestra , murderer of Agamemnon, Elektra’s father. To the exclusion of background narrative, all is subordinated to Elektra’s revenge. And the opera is expressionist in in its representation of brutal, violent horror.

Richard Strauss’s (1909) opera Elektra was his first collaboration with librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Recreating the ancient Greek myth, the opera is modernist in its focus on Elektra and her mother Clytaemnestra , murderer of Agamemnon, Elektra’s father. To the exclusion of background narrative, all is subordinated to Elektra’s revenge. And the opera is expressionist in in its representation of brutal, violent horror.

Musically Elektra is complex and challenging for both singers and orchestra, the soprano role of Elektra , like Salome, one of opera’s most demanding. Elektra’s use of ‘dissonance, chromaticism, and fluid tonality’, similar to that in Salome (1905), moves beyond it to mark Strauss’s furthest excursion into modernism. As with Salome’s final dissonnant chord, the ‘bitonal’, extended ‘Elektra chord’ is infamous. Characters -as in Salome– are distinguished in music through leitmotives, or chords.

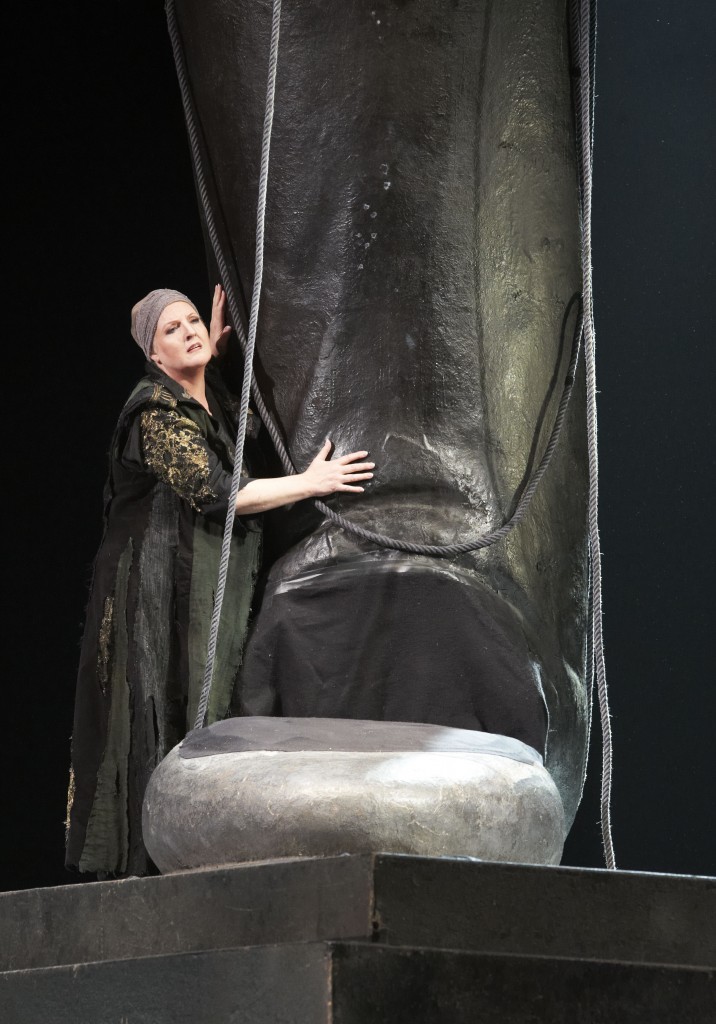

In Vienna State Opera’s production, dominating the stage is a giant statue of Agamemnon, huge legs like tree trunks, his head lying nearby decapitated. One leg bears down on a globe, crushing it like an eggshell. Agamemnon -like Caesar- bestrode the narrow world like a colossus; and his murder and its consequences overshadow and define the opera. Elektra performs her daily ritual of remembrance. She lays down at his feet, calls on him, swears to avenge him: blood will flow from his murderers like jugs knocked over.

Linda Watson as Elektra is unfeminine- butch, lumpen- in oversized loden army coat, grungy military fatigues and beanie. Watson, who sang Brunnhilde in Thielemann’s Wagner Ring cycle at Vienna State Opera, has all the vocal power as well as sensitivity the tragic role needs. Elektra has become the outsider, whom we see goaded by the palace servants. Later she’s ashamed, before Orestes, in her self-perceived ugliness, all her youth and beauty sacrificed in her vengeful crusade.

By contrast, as Chrysothemis, Anne Schwanewilms appears shapely and elegant in a coutured outfit, trailing white scarf, and matching beret. Her warning to Elektra of her mother’s plan to lock her away is scorned. Chrysothemis’ plea is for compassion and compromise. Her mission- upset by Elektra’s revenge-lust – is reconciliation, to enable her to fulfil her life: to live to have children. Schwanewilms unbuttons to reveal a bright red top covering her bosom: ‘She will have children’. Schwanewilms is a softer, lighter soprano; she’s more human, and feminine. But she can hit the high notes, as when she’s describing herself as a mother figure.

Clytaemestra complains she has no good nights, (‘Ich habe keine gute Nachte’). Like a Lady Macbeth, she’s tormented by her endless dreams. Mezzo-soprano Agnes Baltsa appears on a platform erected by metal-helmeted soldiers, as if in a gothic sci-fi epic. Baltsa, a stunning ice-blonde, wears a long shimmering black evening gown with head piece. Baltsa has tremendous stage presence, lithe and glamorous in contrast to the dowdily dressed Watson. Elektra, protesting she too is a goddess, persuades Clytaemestra to come down from her plinth. Clytaemestra is hoping to engage Elektra by confiding her nightmares to her; she’s attempting to appease the gods. But Elektra replies cryptically , ‘When the right victim falls beneath the axe, you’ll dream no longer’. Of Orestes, Clytaemestra dismisses news of Elektra’s brother’s return, ‘What have I to fear; he lives with the dogs’. In their bitchy cat and mouse exchange, Clytaemestra’s refusal to leave her partner Aegisthus finally provokes Elektra to reveal her true feelings: ‘What must bleed? Your own neck!’

Clytaemestra complains she has no good nights, (‘Ich habe keine gute Nachte’). Like a Lady Macbeth, she’s tormented by her endless dreams. Mezzo-soprano Agnes Baltsa appears on a platform erected by metal-helmeted soldiers, as if in a gothic sci-fi epic. Baltsa, a stunning ice-blonde, wears a long shimmering black evening gown with head piece. Baltsa has tremendous stage presence, lithe and glamorous in contrast to the dowdily dressed Watson. Elektra, protesting she too is a goddess, persuades Clytaemestra to come down from her plinth. Clytaemestra is hoping to engage Elektra by confiding her nightmares to her; she’s attempting to appease the gods. But Elektra replies cryptically , ‘When the right victim falls beneath the axe, you’ll dream no longer’. Of Orestes, Clytaemestra dismisses news of Elektra’s brother’s return, ‘What have I to fear; he lives with the dogs’. In their bitchy cat and mouse exchange, Clytaemestra’s refusal to leave her partner Aegisthus finally provokes Elektra to reveal her true feelings: ‘What must bleed? Your own neck!’

‘Orestes is dead!’ The news, to Clytaemestra’s jubilation, determines Elektra to act alone, unable to enlist Chrysomesis in her plans.

But Orestes appears to Elektra disguised as ‘a friend of Orestes’, a messenger of his own death. Albert Dohmen (Orestes) was recently in Vienna as Wotan/Wanderer in Wagner’s Ring , also Flying Dutchman . Dohmen is a tremendous bass/baritone, of international renown, ballast in a largely female cast.( Dohmen’s authority is undiminished, even in a patchwork hooded parka, over a torn, brown leather outfit.) His recognition of his sister – Elektra, ‘So sehe ich sie!’– is one of the opera’s many highlights. ‘No you mustn’t embrace me’, Elektra protests, her hair is dirty, unkempt, ashamed of her lost femininity. They seem to stagger, disorientated, symbolically beneath the legs of Agamemnon. Their being together again is beyond any dream(Traumbild). ‘Stay by me’, their duet, is sung to an exquisitely moving cello accompaniment. Orestes, urged on by Elektra to perform the deed, ‘will do it, without delay’.

But Orestes appears to Elektra disguised as ‘a friend of Orestes’, a messenger of his own death. Albert Dohmen (Orestes) was recently in Vienna as Wotan/Wanderer in Wagner’s Ring , also Flying Dutchman . Dohmen is a tremendous bass/baritone, of international renown, ballast in a largely female cast.( Dohmen’s authority is undiminished, even in a patchwork hooded parka, over a torn, brown leather outfit.) His recognition of his sister – Elektra, ‘So sehe ich sie!’– is one of the opera’s many highlights. ‘No you mustn’t embrace me’, Elektra protests, her hair is dirty, unkempt, ashamed of her lost femininity. They seem to stagger, disorientated, symbolically beneath the legs of Agamemnon. Their being together again is beyond any dream(Traumbild). ‘Stay by me’, their duet, is sung to an exquisitely moving cello accompaniment. Orestes, urged on by Elektra to perform the deed, ‘will do it, without delay’.

We see Aegisthus (Herbert Lippert) led away to his death. There is a horrible groan, or stifled scream. Chrysothemis, announcing their brother has done it, is ecstatic. Her clothes are blood-splattered from the massacre wreaked by Orestes’ followers.

In the confusing closing scene Elektra appears dancing ecstatically, trance-like. In the confusion, they’re pulling on ropes, scaling the enormous statue. (What if it falls, we nearby audience wonder.) Elektra is now binding ropes around the base of the giant Agamemnon statue, as if it were a captive Gulliver. Both daughters are dancing wildly. There’s a fearsome, dissonant chord- dire, ominous, chilling- repeated on the trumpets. Orestes stands on the sculpted head of his father, Agamemnon. Elektra collapses beneath her father’s towering legs. Unable to move, ‘the burden of happiness’, her hopes of renewal, are illusory; the web of fate is inescapable.

With the principal cast predominately women, it was appropriate to have a woman conductor. Simone Young directed Vienna State Opera orchestra in the packed pit, orchestra augmented by two harps, with very unusual percussion including tam-tam, tambourine, cymbals, castanets, glockenspiel, celesta, and 6-8 timpani. Young’s impassioned conducting rightly received enthusiastic applause. As did the leads of an exceptional cast, Baltsa, Schanenwilms, Dohmen, and especially Linda Watson. Directed by Harry Kupfer (61st production with this set), Hans Schavernoch’s stage design deserves mentioning, a rare achievement: minimalist, highly effective symbolism, timeless.

27.06.2012

Photos: Linda Watson (Elektra); Agnes Baltsa (Clytaemnestra) ; Albert Dohmen (Orestes)

(c) Wiener Staatsoper / Michael Pohn

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog