Cream moiré satin curtains invite us in as Vienna State Opera orchestra’s plucked strings and flutes open Verdi’s magisterial overture. But the proscenium arch within is only an antiquated stage set. The red drapes and stucco laurel garlands, as are the pillars in a brown green roccoco style, are obviously painted. Stale! This is the 83rd performance in this staging (Emanuele Luzzat), in Giannfranco de Bosio’s production. Time for a change.

Cream moiré satin curtains invite us in as Vienna State Opera orchestra’s plucked strings and flutes open Verdi’s magisterial overture. But the proscenium arch within is only an antiquated stage set. The red drapes and stucco laurel garlands, as are the pillars in a brown green roccoco style, are obviously painted. Stale! This is the 83rd performance in this staging (Emanuele Luzzat), in Giannfranco de Bosio’s production. Time for a change.

Fortunately, this cast, mostly new to me, are very good, Vienna State Opera Orchestra, and especially Chorus, excel under veteran Verdian conductor Jésus López-Cobos.

Swedish King Gustaf III, in his opening aria, sings power is only good if it seeks virtue in glory. Yet, immediately, he’s thinking of Amelia ‘and forgets all else.’ Gustaf sings of his love for her, she, his best friend’s wife.

Kamen Chanev (short black hair, rather boyish features) has a superb, sonorous tenor. The Chorus background -perhaps ironically- chant ‘he thinks of nothing but our good.’

In his first scene with Ankarström (George Petean), Gustaf is warned he isn’t safe there. The King sings of his duty: the love of his people protects him, and God is on his side. Ankarström (Petean a fine baritone) emphasises the lives of thousands depend on him. Will the love of his people always protect him? Hate is more vigilant than love. Here, Verdi underlines Ankarström’s loyalty, thus making Gustaf’s secret betrayal -he’s in love with Ankaström’s wife- more dramatically problematic. Petean -older looking, portly, sleeked black hair, goatee beard- effortlessly sustains impressive high notes.

We hear of the fortune teller Ulrica who the King saves from banishment. ‘She tells beautiful ladies their fortune, but is in league with Lucifer’-according to the page boy Oscar (Hila Fahima) a high- pitched soprano. But the King will go in disguise.

To strident chords, stabbing cellos, Monica Bohinek’s Ulrica, witch-like, has long black tressled hair. It’s the same dull set, now with a decorative oven and cauldron. Bohinec’s mezzo has what it takes vocally, but in black lace, gypsy shrouds, so melodramatic! Is this the fault of Verdi’s neo-gothic scene? (To a ‘long live the sorceress’, she disappears in a cloud of smoke.) But in her aria ‘Where pale moonlight falls …where criminals breathe their last’, explaining where Amelia’s to find the herb she prescribes, Bohinec is lyrical, sings tenderly.

Amelia seeks a remedy for her dilemma, her love for Gustaf the King. Amelia’s plea ‘purify my heart and find peace’ is sung with ardour and feeling by Sondra Radvanovsky- overheard by the King in disguise. The trio of Gustaf left, Ulrica, and Amelia right stage is a wonderful Verdian moment.

In the publically staged fortune telling, The King , in sailor’s disguise, seeks to know ‘whether the sea and my beloved are true to me’. This is a dream role for a tenor, and Chanev, glorious, over-confident- but Ulrica knows bold words will end in tears- is a virtuoso display of the tenor’s art. ‘Know you will die by the hand of a friend. Thus it is written’, sings Ulrica, but Gustaf treats it as a joke, and bounces around mockingly. ‘And the first to shake his hand today’ is the hand of his most trusted Ankarström. But against a terrific Verdian chorus affirming their King- the voices of the conspirators, their time will come- Gustaf will defy his fate.

Un Ballo in Maschera is classic Verdi with a surfeit of big moments. And the music is ravishing. Such as Amelia’s aria ‘This terrible place has both crime and death’ (at the executioner’s ground). ‘Though I may die here, I must do it.’ Radvanovsky, who’s previously sung Amelia here, is excellent, powerful in her wavering. ‘But what if the herb erases his image from my heart?’ The aria sung to a plaintive oboe, Sondra kneeling, was well applauded.

Then the duet with Gustaf, where Amelia sings to him, she must end the torment. But he pleads, does she know that his heart, ever in pain, will cease altogether. How many sleepless nights he’s prayed she would hear him. She- Heaven help me. Go! Say no more! But Gustaf persists, he would give his life for a single word… And she demures.’Yes! I love you! Protect me from my heart.’ Kamen Chanev responds with a heavenly cry, a sustained top note, ‘You love me! Nothing remains but love.’ She’d rather die than never be his. Amelia, do you love me? Yes! These two are resplendent.

Ankarström arrives, ironically to protect the King from the plotters. Amelia, far stage, is disguised in a veil. Veils are inrinsic and instrumental to the plot, however curious that may now seem to us. (While the King escapes in Ankarström’s cloak, Ankarström offers to lead the mystery lady to safety, the two silent, looking askance.)

End of Act II, Chorus and ensemble are masterly, typical of late Verdi. Chorus sing mockingly, Ankarström is having a secret assignation with his wife. (Amelia sings, the man I adore has dishonoured me.) The mocking Chorus, reminiscent of Falstaff (Chimes at Midnight), chant ‘the tragedy has turned into a comedy that will amuse the city’.

In the complex Act 3, Ankarström threatens to kill Amelia, who begs that she see her child for the last time. In her aria, that her son should close the eyes of the mother, Radvanovsky intensely moving, soars to the highest notes. But she’s also pleading for clemency. Ankarström, surely moved, pities her tragic plight, decides another’s blood must play. Petean’s baritone impresses in another terrific aria. It was he who destroyed his happiness! This is no way to reward the loyalty of a friend. A flute accompaniment leads into a lament of the bliss no longer his with Amelia in his arms. It is all past. Ankarström joins in a pact with the conspirators, their rousing march ‘Revenge, Unite!’ reminiscent of Don Carlo and Rodrigo’s oath. (Amelia appears opportunely as the conspirators are drawing lots to assassinate the King.)

In the complex Act 3, Ankarström threatens to kill Amelia, who begs that she see her child for the last time. In her aria, that her son should close the eyes of the mother, Radvanovsky intensely moving, soars to the highest notes. But she’s also pleading for clemency. Ankarström, surely moved, pities her tragic plight, decides another’s blood must play. Petean’s baritone impresses in another terrific aria. It was he who destroyed his happiness! This is no way to reward the loyalty of a friend. A flute accompaniment leads into a lament of the bliss no longer his with Amelia in his arms. It is all past. Ankarström joins in a pact with the conspirators, their rousing march ‘Revenge, Unite!’ reminiscent of Don Carlo and Rodrigo’s oath. (Amelia appears opportunely as the conspirators are drawing lots to assassinate the King.)

Now a screen depicts the interior of the palace. Gustaf resolves to give up Amelia, and to send her and Ankarström to their homeland. Chanev, with his beautifully rich tenor -but eschewing vibrato and false emotion- sings that he has signed his own sacrifice.(Does he have to do it all! Verdi’s familiar unenviable sovereign.) But forced to leave her he will never forget her. Indefatigably, he’ll go to the ball anyway. He’ll see Amelia for the last time and his love will be kindled by her beauty. Sung by Chanev with consummate prowess, thrilling!

The masked ball: the curtain rises on the cleverly painted sets, the trompe l’oeil galleries, leading into a recessed ballroom area. But the costumes are for real: splendid, spectacularly colourful. The black-cassocked Gustaf confers in earnest with a masked Amelia. We see his black-clad figure, with a blood-red patch, falling. Verdi’s strings parody the ball’s minuet theme background. Gustaf dying, forgives Ankarström, admits he loved his wife, but didn’t violate her honour. Ironically, tomorrow she was to leave. The Chorus, no longer ironic, sing ‘God save his noble heart.’ And what a rousing Verdi chorus- Oh! night of terror!-Vienna State Opera’s forces inspired under Jésus López-Cobos. P.R. 13.O9.2013

Photos: Monica Bohinec (Ulrica); Sondra Radvanovsky (Amelia);

Featured image: Monica Bohinec and Mihail Dogotari (Christian)

(c) Wiener Staatsoper/ Michael Poehn

Monthly Archives: November 2013

Verdi’s Otello

Verdi has transformed Shakespeare’s play into an operatic masterpiece, inspired by the characters, respecting the original plot, but alchemising Shakespeare’s rare metal into a musical drama on a different level. And because Verdi’s orchestration can point up, add to, the musical drama enacted on stage, the opera is surprisingly economical, with no surplus scenes.

Verdi has transformed Shakespeare’s play into an operatic masterpiece, inspired by the characters, respecting the original plot, but alchemising Shakespeare’s rare metal into a musical drama on a different level. And because Verdi’s orchestration can point up, add to, the musical drama enacted on stage, the opera is surprisingly economical, with no surplus scenes.

There’s no overture, but Verdi’s tempestuous orchestration depicting Otello’s ship caught in a storm from Venice, is ominous:’a dark spirit is in the ether.’ The chorus are on tremendous form, as is Vienna State Opera Orchestra under Dan Ettinger.

The minimalist staging (directed by Christine Mielitz), based on a white cube illuminated platform, subtly veils steel- mesh panels for the intimate scenes. The costumes are unfussy, vaguely modern, the sets unproblematic, not distracting. The drama and colour is on stage.

The first surprise is the ‘Iago’ character, dominant from the opening, and in Verdi, more explicit as to his reasons for plotting against Otello. Jago is out for revenge, passed over by Cassio who’s promoted to Captain. Against expectations it is superstar Dmitri Hvorostovsky cursing the thick-lipped Moor. ‘The world of a woman is untrustworthy.’ Jago , the soldier’s man, is a mysoginist, always manipulating women. Although Jago pretends to love Otello, he despises the Moor who demoted him. Hvorostovsky is swaggeringly confident, good looking with long white -platinum hair, dressed in a dark leather coat over black outfit. Verdi’s Jago, unlike Shakespeare’s more abstruse character, openly declares to Rodrigo, ‘If I were the Moor I would be on my guard against Jago.’

We see Cassio (Marian Talaba) swigging from a bottle side stage . He sings of Desdemona as the power of the island, and yet so modest. Jago knows that if Cassio gets drunk he loses it. So Jago rabble-rouses the soldiers to drink , stirs up Rodrigo against Cassio-‘the quarrel to spoil Otello’s first night of love.’ (‘Put down your swords’, thunders Otello; and demotes Cassio.)

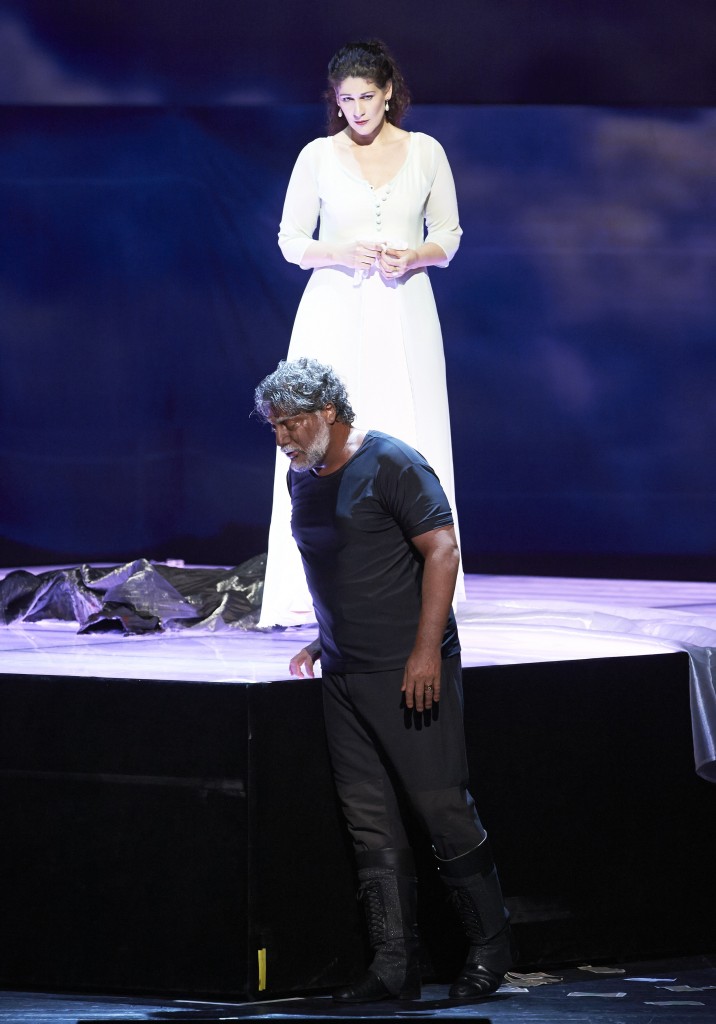

Otello (José Cura) is the second surprise- grey-haired, white beard, the older man. A Shakesperean Othello would be negro -an opportunity for under-used black talent- as surely in the elitist opera world. But Cura wins on merit -a moving, disturbing portrayal, magnificently sung. (And, sorry, must a north African be black?) He’s dressed in distressed long black leather, in his first scene with Desdemona. To a long cello solo , Otello sings how, in the black night, his raging heart is subdued; Desdemona (Anja Harteros) of how many hardships preceded their great love. Harteros is a powerful soprano, endearing as Desdemona . Tall, noble, unaffected, dressed in a long , white satin gown, she has a purity of tone, her virtuoso soprano in reserve.

Cura and Harteros are natural, truly complementary. She listened with bliss to his tales of woe, with terror his battles. ‘You loved me for my suffering; I loved you for your compassion.’ In their duet, their loving relationship seems more developed than in Shakespeare. Presciently, ‘his bliss is so great he might never be this happy again.’ Desdemona, centre stage in white, stands over him, soothes his head. Cura’s all in black. These two are very convincingly in love.

Which makes Jago’s treachery all the greater, Jago knowing Otello lives only for her. Jago conspires to advise the now demoted Cassio to persuade Desdemona to intercede for him with Otello. But while Cassio is talking to Desdemona, Jago incites Otello’s jealousy.

Verdi’s aria for Jago is masterful, modern in its psychological insight into the villain’s motives. Jago from the baseness of an atom, was born wretched, sings defiantly, ‘I am a villain because I am a man and feel the primeval in me.’ And darkly ‘existentialist’, believes man is the plaything of fate, from the cradle to the grave. After so much mockery comes death! And then…Heaven is a myth. It’s a Machiavellian agenda, shockingly modern. Hvorostovsky glowers triumphantly.

Verdi’s aria for Jago is masterful, modern in its psychological insight into the villain’s motives. Jago from the baseness of an atom, was born wretched, sings defiantly, ‘I am a villain because I am a man and feel the primeval in me.’ And darkly ‘existentialist’, believes man is the plaything of fate, from the cradle to the grave. After so much mockery comes death! And then…Heaven is a myth. It’s a Machiavellian agenda, shockingly modern. Hvorostovsky glowers triumphantly.

So, observing Desdemona and Cassio talking, ‘My lord, did Cassio know Desdemona before you married’, Jago asks Otello. – ‘Are you my echo, putting thoughts in my head?'(Otello) Yet, Jago, implanting these insinuations, has the chutzpah to advise Otello, ‘Beware, my lord of jealousy! It is a dark hydra- it poisons with its venom.’ First the investigation, the proof, insists Otello, Cura’s rich tenor.

Desdemona, ‘an honest soul, fails to see deception’ (sing a heavenly choir). Is she too good to be true? So Verdi has children singing- perhaps ironically- Desdemona is ‘like a sacred image they adore’. Yet Desdemona -the epitomy of innocence- unwittingly promotes Cassio’s cause seeking Otello’s pardon. ‘Not now.’-‘Why so irritable.’ What troubles him?’ So Desdemona, guiless, isn’t guiltless. Harteros’s portrayal is all too human, rather than saintly.

In one of the opera’s great ensembles, on opposite sides of the stage, Jago is persuading his wife Emilia to steal a handkerchief from Desdemona, her mistress. Meanwhile Desdemona is trying to soothe Otello. We hear fragments of dialogue, ironically in contrapunct: ‘Suspicion is worse than the crime itself.’ Otello, brooding, wants to be left alone. ( In his aria, sings darkly, this spells the end of Otello’s glory; but wants proof.)

Hvorostovsky, in Act 2’s dream scene, is a highlight. Reacting to Otello’s insistence of proof of Cassio: ‘the terrible deed is always hidden.’ Otello listens intently as Jago relates how he heard Cassio calling out Desdemona’s name in his sleep. ‘Sweet Desdemona, we must hide our love…’ is sung exquisitely, passionately by Hvorostovsky. And ‘I curse the fate that gave you to the Moor’, sung from the heart, as if Hvorostovsky’s Jago is expressing his own feelings. (He is!) The dream faded, finally, Jago’s coup-de-grace, Desdemona’s handkerchief.‘This was the handkerchief in Cassio’s hands.’ Otello’s blood turns to ice: this land shall soon unearth a thunderbolt, Otello swears by the god of vengeance. The scene is a triumph for Hvorostovsky and Cura.

Otello’s interrogation of Desdemona (Act3) is another a high point. The stage is a cage effect, the white square platform -suggesting the marital bed- has a meshed guard in front. Harteros greets him: May God give you joy. He, give me your ivory hand . ‘As yet it bears no traces of pain or age. And with this same hand she gave her heart to him.’ But while he asks her for her handkerchief, she, innocently, wants to speak of Cassio. ‘It was embroidered by a sorceress. Have you lost it?’ Then she, with supreme irony,’You are playing a game with me to distract me from Cassio.’-‘Tell me who you are.’- ‘The faithful wife of Otello.’ Harteros is on her knees, head slumped. He is stalking the cage like a prisoner. She, heartrendingly, ‘behold the first tears (that grief has ever wrung from me.’ He accuses her as a common whore. She’s cowered, shrunken. Then will apologise to her. Still she’s the common whore who is Otello’s wife. She fights him off as she exits. He’s left sobbing painfully. These exchanges (Boito’s libretto) ,shockingly modern, could be from ‘Scenes from a Marriage’. Then Otello’s aria- Cara sitting behind the meshed-wire cage, ‘But you have robbed me of the illusion that nourished my soul.’

Desdemona’s two arias The Willow Song and Ave Maria are sung by Harteros with great feeling. To an exotic oboe, she requests Emilia lay out her wedding outfit; sings of how a girl once sang, wept with bitter tears, the gloomy willow will be her bridal garland. Then ‘He was born for glory, I was born for love’; and to love him to die. Harteros in white- the guilty Emilia (Monika Bominek) hooded in black -soars ‘Oh, Emilia!’. Harteros’s soprano is tempered with an affecting simplicity, singing Ave Maria. Pray for the sinner, the innocent. Pray for those who bear abuse, suffer tragic fates. Pray for us always, even in the hour of death. Harteros is on a deserted stage, kneeling, a figure of suffering. For once no applause was possible.

Desdemona’s two arias The Willow Song and Ave Maria are sung by Harteros with great feeling. To an exotic oboe, she requests Emilia lay out her wedding outfit; sings of how a girl once sang, wept with bitter tears, the gloomy willow will be her bridal garland. Then ‘He was born for glory, I was born for love’; and to love him to die. Harteros in white- the guilty Emilia (Monika Bominek) hooded in black -soars ‘Oh, Emilia!’. Harteros’s soprano is tempered with an affecting simplicity, singing Ave Maria. Pray for the sinner, the innocent. Pray for those who bear abuse, suffer tragic fates. Pray for us always, even in the hour of death. Harteros is on a deserted stage, kneeling, a figure of suffering. For once no applause was possible.

Dan Ettinger’s double-basses prepare us as Otello approaches her veiled bed- a dark presence violating this spiritual purity . Cura, swarthy in black , cold measured restraint, like a serial killer, ‘If you remember any sin, now’s the time to atone…’ But she insists, she doesn’t love Cassio. The veil collapses. The strangling is very, horribly real.(Emilia arrives announcing Casio has killed Rodrigo. Casio lives.) She dies blameless. Cura, over the body laid out, ‘how pale, silent, beautiful you are: born under an evil star, Desdemona died.’ There is absolute silence in the House. A bassoon bleats mournfully; Otello craves one more kiss before dying. With tenderness and compassion, Verdi expresses the fragility of being human. P.R.20.09.2013

Photos: José Cura (Otello) and Anja Harteros (Desdemona); Dmitri Hvorostovsky (Jago); Anja Harteros (Desdemona); Dmitri Hvorostovsky headline

(c) Wiener Staasoper/ Michael Pӧhn