Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten (The Woman without a Shadow) premiered at Vienna State Opera (October 10, 1919). Critics and audience had problems, as I did, with Hofmannsthal’s complex and heavily symbolic libretto. The opera is still a challenge to stage even for major opera houses, requiring a huge orchestra, and elaborate sets. Outstanding Vienna State Opera productions include Clemens Kraus, Bohm and Karajan. M D Franz Welser- Möst’s, in a revival of Robert Carsen’s 1999 production, must bear comparison.

Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten (The Woman without a Shadow) premiered at Vienna State Opera (October 10, 1919). Critics and audience had problems, as I did, with Hofmannsthal’s complex and heavily symbolic libretto. The opera is still a challenge to stage even for major opera houses, requiring a huge orchestra, and elaborate sets. Outstanding Vienna State Opera productions include Clemens Kraus, Bohm and Karajan. M D Franz Welser- Möst’s, in a revival of Robert Carsen’s 1999 production, must bear comparison.

The opera is set in a mythical empire. The Empress is not human, a spirit captured as a gazelle. She assumes human form, mastered by the Emperor. But she still has no shadow, a symbol of her inability to have children. She must gain a shadow, or be reclaimed by her father, and the Emperor turned to stone. The Empress descends, accompanied by her Nurse, disguised as humans, seeking a woman willing to sell her shadow: a Dyers Wife is contracted and promised lovers and luxury. But ultimately the Empress ‘will nicht’; she refuses to deny the wife her unborn children. (The Empress’s renunciation liberates herself and reconciles both couples.)

Taken literally, the story is both over-complicated and preposterous. But seen as a psycho drama, its language is embedded in ‘unconscious’ symbolism. The opera is, rather, a tale of motherhood from the perspective of Freud’s psycho analysis, (explains Ian Burton) Thus, out of guilt feelings for her father, the Empress is made barren. She casts – the symbol for it – no shadow. In her efforts to create this shadow, she undergoes a series of painful tests.

Hofmannsthal’s libretto is full of dreams and dream symbolism . Characters are constantly explaining their dreams, and repressed wishes and desires. In Die Frau ohne Schatten the dream of the Empress is central to the plot. And the whole of the third Act could be seen as a continuous dream world.

Further, Hofmannsthal was influenced by Otto Rank, Rank’s concern being with the individual ‘self’, and the threat of its annihilation in death. Man seeks to annul this fear through erecting a series of myths of Unsterblichkeit, man’s immortality.

The theme of man’s self-renewal – staying young through our children – is central. Also Rank (Doppelganger, 1914) argues for the significance of the shadow – derived from oriental sources- as a symbol for the soul in art and literature.

Rank himself acknowledged the material for Strauss’s opera and Hofmannsthal’s libretto. The complicated psychic experience of the Empress runs from her dream of the Emperor turning to stone; and lets her find the reason for her dejection, finally in her relationship to her mysterious father Kerkobad. The Empress, by refusing the wife’s shadow, discovers her own self, her humanity, ‘new birth’. (Burton)

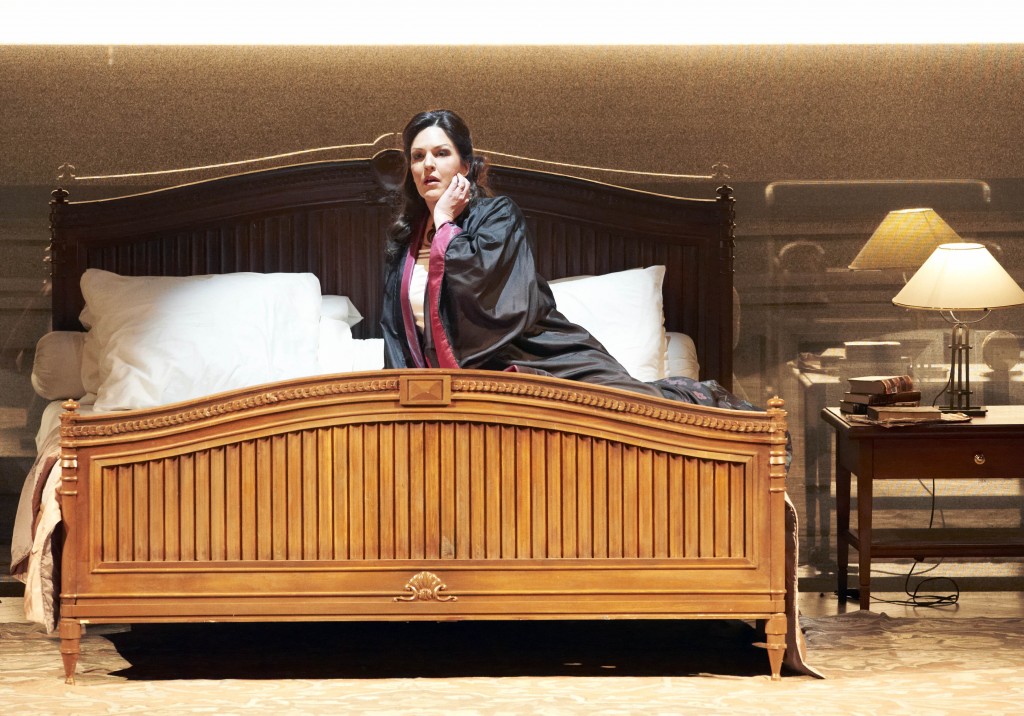

So the stage design needs to hint at this ambiguous sub-text. Vienna State Opera’s set, with rich jugendstil early 20th Century furnishings, reminded me of an enlarged psychoanalysts’s study: the art nouveau bureau on the left, the oriental carpet foreground. And the bed, ornately embellished is centre stage in Act 3, perhaps suggesting a living nightmare. By no coincidence, the Priest (Wolfgang Bankl), bears an uncanny resemblance to Freud, wearing similar spectacles and white coat- as does the Nurse (Birgit Remmert), also carrying a medical folder.

A screen divides the stage, as if to mirror the front half of the set. The sides of stage are white to reflect the shadow of the Emperor in Act 1. Phantom shadows effect a nightmare quality, reflecting the subconscious of the protagonists.

Surrealism is also evidenced (Act 1) in a recreation of a silent 1920s surrealist film, the Empress’s face is seen in close up, as she trembles. The image enlarges, blown up frighteningly – reminiscent of Dali/ Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou.

The Empress (Adrianne Pieczonka) immediately entrances with her high, bird-like dramatic soprano, (with extended coloratura passages of trills and runs from the first solo). Hers is a purer, sweeter soprano- in contrast to the more frenetic, highly strung Evelyn Herlitzius (dyer’s wife). The Empress has a bird-like enchantment, as befits her previous life as a gazelle, and metamorphosing spirit of nature.

Evelyn Herlitzius’s soprano is also a thing of wonderment, her immense power needed against Strauss’s heavy orchestration. But with a nervy quality, sometimes shrill, a voice for the 20th century, attuned to troubled times. Herlitzius is phenomenal, but unsettling: a major dramatic performance. The parts of Dyer’s Wife and Nurse (Remmert) are practically unsingable without some cuts- sanctioned by Strauss himself- second and third Acts being especially difficult. No five singers worldwide can sing these scores in their entirety, argues conductor Franz Welser-Möst.

Herlitzius is phenomenal, but unsettling: a major dramatic performance. The parts of Dyer’s Wife and Nurse (Remmert) are practically unsingable without some cuts- sanctioned by Strauss himself- second and third Acts being especially difficult. No five singers worldwide can sing these scores in their entirety, argues conductor Franz Welser-Möst.

Of the male principals, American tenor Robert Dean Smith, formidable as Emperor capably handles the many passages requiring his uppermost range, especially Act 2’s extended solo scene.

Wolfgang Koch (Barak) the distinguished dramatic baritone is perhaps too mellifluous as the old Dyer; but Barak’s is a therapeutic, healing role.

In the closure there is a fantastic moment as light enters the stage through a high back door. The Emperor and Empress embrace , as if they’ve come through some psychic trauma. Barak and his wife are reunited and she regains her shadow. Young couples – their unborn children – form a circle around the stage. The stage is flooded with white light , perhaps exorcising the dark world the of subconscious doubts and trauma. The coming together of both pairs is as if ushering in a Brave New World: mankind devoid of its destructive elements. And Strauss’s use of C Major in the Finale -the purest key in music – enhances this heavenly idealisation.

Welser-Möst describes how Strauss takes the listener by the hand from room to room in this fantastic fairytale world. Everything is highly characterised by orchestral colour to lure us into this dream world. The music of the Emperor and Empress is made unworldly through unusual instruments, glass harmonica, and celesta; likewise the Falcon music is highly colourful; by contrast earthy, simply structured, for Dyer and his Wife. Strauss challenges the conductor to bring together these divergent musical worlds seamlessly. In a performance in a thousand , Welser-Möst elicited passionate, luxuriant sounds from his Vienna State Opera Orchestra.

20.03.2012

Franz Welser-Möst, interview Oliver Lang ; Ian Burton, Traume und Geschichte

Photos: Adrianne Pieczonka (Empress); Wofgang Bankl (Priest), Birgit Remmert (Nurse); Evelyn Herlitzius (Dyer’s Wife), Adrianne Pieczonka (Empress)

(C) Wienerstaatsoper/ Michael Pöhn

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog