Consider the fate of Lucia di Lammermoor. Manipulated by her unscrupulous brother Enrico facing financial ruin, she must marry the rich and influential Arturo. But Lucia is still grieving for her murdered mother; and she’s in love with Edgardo, who saved her life. But Edgardo is her brother’s sworn enemy, Enrico having killed Edgardo’s father and aggrandised his lands.

Consider the fate of Lucia di Lammermoor. Manipulated by her unscrupulous brother Enrico facing financial ruin, she must marry the rich and influential Arturo. But Lucia is still grieving for her murdered mother; and she’s in love with Edgardo, who saved her life. But Edgardo is her brother’s sworn enemy, Enrico having killed Edgardo’s father and aggrandised his lands.

Lucia is the victim of patriarchal conspiracies. Tricked into an arranged marriage she faces ‘a living death’. Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor– based on Sir Walter Scott’s gothic novel- is more than a Scottish intrigue with an Italian twist. Significantly, Edgardo offers, before going abroad, to make peace with Enrico, out of love for Lucia. Edgardo is cast, in Donizetti’s opera, as a noble figure pitted against the ritual feuding, cult of machismo personified by Enrico, who ‘lives by the sword’. Edgardo is the new ‘romantic hero’ prepared to sacrifice his family’s (patriarchal) claims for love. In the tragedy love prevails, albeit posthumously.

Vienna State Opera’s Lucia, Diana Damrau, red-haired, in a green silk gown, reminded me of Rosetti’s Pre-Raphaelite paintings. In Scene 2 (Ravenswood Park) Lucia is awaiting Edgardo- where one of his jealous ancestors once stabbed his wife. Lucia sees her ghost- a presentiment. Regardless, Lucia affirms Edgardo ‘the light of my life… with glowing passion, he swears his eternal love for me’. It’s all very pleasing, but -at this point- Damrau seems as if holding back, top note a little unstable. She reproaches Edgardo ‘Tomorrow he leaves the country, and he’d leave me in tears’. Her duet with Edgardo is powerfully rendered. Their love must remain secret. Edgardo (Piotr Beczala), is consumed with rage:’He took my father, my inheritance: what more does he want, blood?’ They vow allegiance as man and wife in love.

Beczala, handsome, dark-haired, makes a dashing Edgardo, with sword hanging by his side. Beczala is a very impressive lyric tenor. A regular at Vienna State Opera, he received frequent ovations. With Edgardo standing over Lucia , seated on the park bench, they make a good-looking couple- for a change! Their duet, a highlight, was well applauded.

Baritone Marco Caria is also very impressive as Enrico. He’s a baritone of real calibre: convincing in his rhetoric, appealing to Lucia as a brother. Lucia accuses Enrico: only God can forgive his actions. And, rejecting marriage to Arturo, she protests she has sworn allegiance to another. ‘Enough!’ Enrico brandishes the forged letter proving Edgardo’s infedelity.

Lucia is crestfallen. In her aria, Damrau movingly suggests the beginning of the unravelling of Lucia’s mind. ‘My heart is broken… I have suffered. My hopes depended only on him. I feel as if I were dead. That fickle man now loves another’, she reproaches herself. ‘You were blinded’, Enrico twists the knife. ‘Save me!’, he pleads otherwise his fate is sealed. Enrico’s rhetoric insidiously reverses the argument. She, Lucia, is wielding the axe against him if she doesn’t marry Arturo. Yet she’s directing ‘the bloody axe’ against herself. ‘Oh, ill-fated love’, she pines.

Raimondo piles on the pressure: stressing Lucia’s resposibilities to family. ‘Your brother’s life and happiness depend on you alone. Be silent, you have no respite.’ Then, on a tremendous sustained note, ‘You are blessed; such a sacrifice will cause great joy in heaven’. Sorin Coliban’s superb baritone seems almost sympathetic. Lucia tries to rationalise: Edgar had betrayed her. She’s caught in a patriarchal trap.

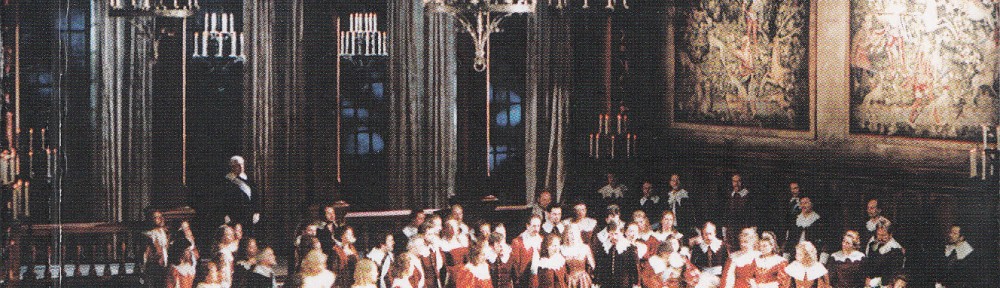

The wedding ceremony in the Great Hall of Ravenswood is magnificently staged. There are authentic-looking tapestries on walls either side, oak panels, suspended candelabra, dignitaries dressed in rich shades of red and gold, swords crossed for the entrance – it would do justice to a Hollywood film set. Edgardo gatecrashes the wedding. Lucia has to choose between ‘life and living death’. Raimondo separates Enrico and Edgardo:’He who lives by the sword dies by the sword’. Edgardo, handwriting is tested; Enrico’s forgery is exposed.

In the so-called ‘mad scene’, Lucia enters the Hall imagining she is going through her marriage with Edgardo. Damrau, dressed in a white night gown, flecked with blood spots, her hair disheveled. She almost staggers into the Hall, disorientated , with a wild look, as if possessed. Swaying, as if on a tightrope, she makes her way to the altar, where she imagines roses for her wedding to Edgardo.

The extended aria (over three melodies) is an advance exercise in coloratura – a demonstration in belcanto for Damrau- culminating in a formidable dialogue with a flautist. Her runs are responded to and echoed by the flute. It’s meant to show how her mind is cracking up : technically dazzling, but disconcerting. Damrau enacts the scene sympathetically, without histrionics. Ultimately it’s very moving. Raimondo warns Enrico of the danger and seriousness of his sister’s condition. The scene ends with Lucia’s collapse on the edge of the stage. The applause for Damrau was such that you might have imagined the opera ended here.

Not so. In Donizetti’s (text by Cammaroni) dramatic scheme, resentful Edgardo sees the light in the castle. Beczala powerfuly conveys Edgardo’s morbid imagination of Lucia’s wedding celebrations- unaware she’s murdered her husband, driven mad out of love for him. And in the terrible irony of the crypt scene, Edgardo’s vigil, expecting the duel with Enrico, becomes a wake as Lucia’s body is carried in. Edgardo kneels before the altar; Beczala, backed by choir, is tremendous, in the scene’s developing drama.

But there could have been an alternative ending.The Tower Scene (6), has Edgardo swearing vengeance by the spirit of hell. The two rivals, Enrico and Edgardo, will resolve their family vendetta in time-honoured duel. Both singers, like football heroes arm-in-arm, acknowledge audience applause. But machismo isn’t what the opera is about.

Before the interval, house manager warned us Diana Damrau was performing in spite of a cold. Maybe this might account for a slight wavering in her opening scenes. Nevertheless the mad scene was not only a virtuoso demonstration , but also heart rending. Applause was also enthousiastic for Beczala, and Caria’s authorative Enrico. Together with bass Sorin Coliban’s Raimondo’s tremendous stage presence, this quartet could hardly be bettered. Damrau, acknowledging applause, beckoned to the solo flautist who had dueted with her. He exemplified the wonderfully sympathetic playing of Vienna State Opera orchestra under Guillermo Garcia Calvo. The well-used, albeit traditional, sets (designer Pantelis Dessylas, directed by Boleslaw Barlog) are another good reason to commend this production.

24.06.2012

Photos: Marco Caria (Enrico) ; Diana Damrau (Lucia) and Piotr Beczala (Edgardo); Piotr Beczala (Edgardo); Diana Damrau (Lucia)

(c) Wiener Staatsoper/ Michael Pohn

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog