In 19th Century Japan, visitors could have a young woman (musume) for 4 dollars. They rented a house for 25 dollars and a servant for 10 dollars, and so enjoyed in safety the pleasures of marriage: for 39 dollars per month. If the woman pleased him, he could extend the contract. (Samuel Boyer, 1860)

In 19th Century Japan, visitors could have a young woman (musume) for 4 dollars. They rented a house for 25 dollars and a servant for 10 dollars, and so enjoyed in safety the pleasures of marriage: for 39 dollars per month. If the woman pleased him, he could extend the contract. (Samuel Boyer, 1860)

In the opening of Madama Butterfly US Lieutenant Pinkerton is surveying a house to rent for his honeymoon with Cio-Cio-San. She’s to be his temporary wife in Japan -against the advice of Cio-Cio-San’s maid and the US Consul Sharpless.

In Puccini’s tragedy (based on John Long and David Belasco’s play), Cio-Cio-San (Butterfly), falls in love with her Lieutenant, and swept away by her ‘husband’s’ passion, takes his promises seriously. And in Puccini’s (librettists L. Illica and G. Gicosa) sympathetic characterisation- prescient of 20th century awareness of exploitation and alienation- she cuts herself off from her family ties and customs, and identifies with American culture. With tragic consequences.

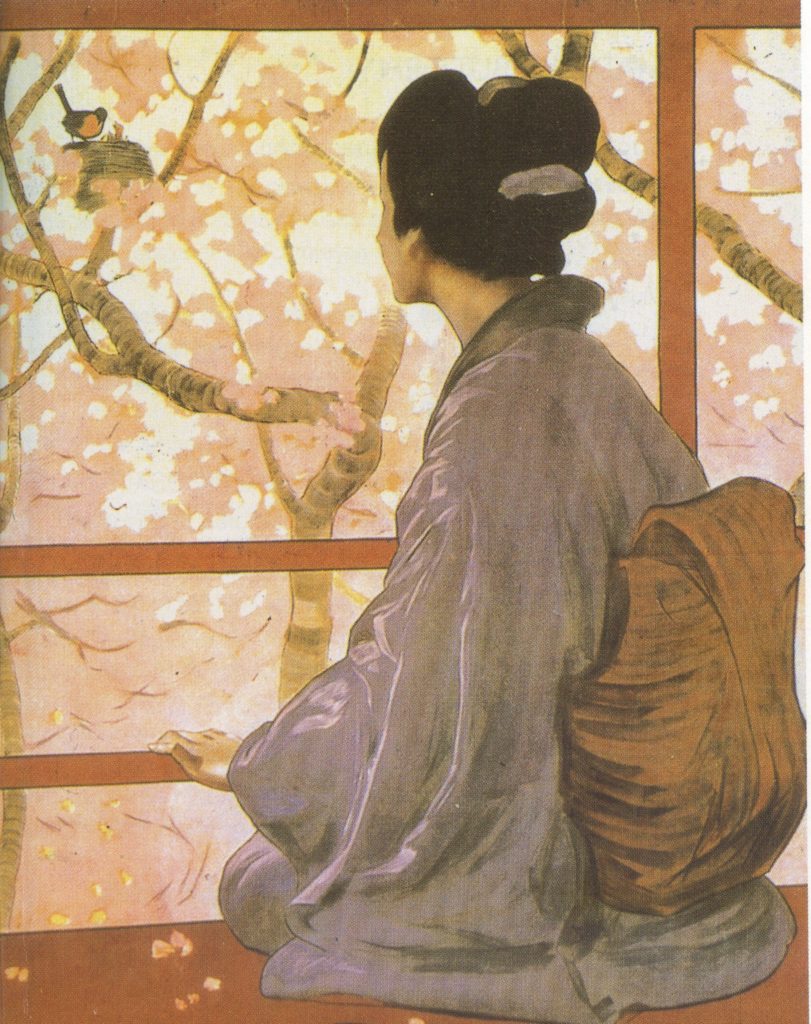

Puccini, as so many late-19th century artists and composers, was fascinated by Japan. The story would make less sense out of historical context, so thankfully Vienna State Opera have maintained the authentic Japanese staging designed by Tsugouharu Foujita, in Joseph Gielen’s classic production. The trees in blossom may seem out of a faded tapestry- pastel colours, oriental motifs- but respectful of Puccini’s obsession with authenticity.

However, against the trend to cast an oriental singer as Cio-Cio-San, Butterfly is sung by Latvian soprano Kristine Opolais, whose credentials for Puccini are impeccable. And, as in the Milan premier, (1904) Pinkerton is sung by an Italian tenor. Piero Pretti, (who sang the Duke to Leo Nucci’s Rigoletto), similarly swaggeringly self-confident, is perfect for Pinkerton: his golden tenor, light but powerful.

The set is like a Japanese mural: cut-out, an overhanging golden willow, with a bridge centre-stage, a drinking well, and veranda. Pretti, clean-shaven, in uniform, boasts to Consul Sharpless (Boaz Daniel) he got it for 999 years, but can cancel any time. In this country, houses, like contracts, are flexible. Pinkerton’s aria is a celebration of masculinity, patriarchy and American power.

In Pinkerton’s ‘Life has a purpose if you pick the flowers on every shore’ the sexually predatory message is clear. Sharpless, well sung by Daniel, is temperate, conciliatory; he warns Pinkerton’s creed easy-going has its complications. Does he love her, his ‘garland of flowers’, or is she like a passing fancy? She has bewitched him, sings Pinkerton, like a figure on a painted screen. She is like a butterfly. He has to catch her even if to break her wings. Sharpless replies, it would be wrong to harm the little thing. They toast to America, Pinkerton to marriage to an American girl .

Cio-Cio-San appears, accompanied by her Geisha friends, Opolais singing ‘She’s the happiest girl in the world. Love called.’ The bridge on which she hesitates is symbolic. She has to turn her back on the things dear to her by Japanese custom. There’s a fragility and ecstatic quality to her voice, softly achieving high notes; Opolais exudes charm. She sings of her life. She came from a well-to-do family. But the storm uproots even the strongest oak. They had to make their living as geishas. Sharpless has never seen anyone as beautiful as Butterfly. ‘Yes, she’s a flower and I have picked it’, now Pinkerton’s property. Opolais’ own beauty justifies the role. She shows him her box of personal possessions. (Not the sacred present from the Mikado to her father.) But, she confesses, she went especially to the Mission to take up her new religion. She’s sacrificed everything for Pinkerton.

The wedding celebration is like a colourful Japanese tableau. Opolais is in a white satin kimono, long, red-bordered train. Uncle Bonze (Alexandre Moisuc) gate-crashes; thunders, she has renounced her faith. Her soul is lost: a stark premonition. Pinkerton orders the Shaman out: will not tolerate shouting in his house. And, in contempt for his hosts, pushes out the house-owner Goro.

In their duet, an extended seduction scene, he urges her not to cry: her relatives are not worth her tears. Viene la sera, evening is coming, everything loving and light. Petri sings he’s overcome by a sudden desire. Opolais, finely choreographed, is like a Geisha mannequin come to life. Disarm all fear, he admonishes. She sings, the stars look down with watchful eyes. He, be not afraid, the sky is saying, be mine. They’re swept away in Puccini’s rapturous ‘night is for love’ refrain. Philippe Auguin brought out the best of the orchestra, Vienna State Opera- the detail essential to Puccini’s descriptive genius. But, however successful individually, together Opolais and Petri lacked a certain symmetry. They seemed to stand physically apart- there wasn’t that emotional interaction.

Act 2 is dominated by Cio-Cio-San. Opolais convinces with tender phrasing, and effortless high notes in the numerous dramatic outbursts, enacting the role with grace and delicacy. In the ‘authentic’ Japanese house, we see Opolais on her futon, a screen behind her. The Japanese gods are lazy, the American ones faster but she fears, they don’t know her address! The last of their money, they’ve been spending too much. But, he arranged for the Consul to pay her rent: he guards his wife, she reasons.

Act 2 is dominated by Cio-Cio-San. Opolais convinces with tender phrasing, and effortless high notes in the numerous dramatic outbursts, enacting the role with grace and delicacy. In the ‘authentic’ Japanese house, we see Opolais on her futon, a screen behind her. The Japanese gods are lazy, the American ones faster but she fears, they don’t know her address! The last of their money, they’ve been spending too much. But, he arranged for the Consul to pay her rent: he guards his wife, she reasons.

No foreign husband has ever returned, forewarns Suzuki (magnificently sung by mezzo Bongiwe Nakani.) Butterfly threatens her, be silent, or- flashing a knife- she’ll kill her. She recalls, how he smiled at her and promised to return ‘when robins build their nests.’ One day a ship will appear- Opolais holds out her hands- but she will not go to meet him. He will call her my little wife, un bel di. (Opolais, in brown, cream kimono, has charm, but is she just a little large for the role?) It will happen, he will return, Opolais top note full throttle.

Sharpless arrives, Daniel blue-suited with boater. Opolais all flustered: we note she offers him an American cigarette. She’s the happiest woman in Japan, she sings, but, in America, when do robins build their nests? He never studied ornithology. Puccini’s libretto bristles, and Opolais and Daniel interacting are lively and naturalistic. Goro tried to marry her off to the rich idiot Yamadoro, she tells him. Opolais brings real life to this too-easily maudlin role. The unhappy girl, chides Sharpless: her blindness saddens him.

Sharpless holds up Pinkerton’s letter, offering to read it. Pretty flower, three years have elapsed . Perhaps Butterfly no longer thinks of him. And to Sharpless, Prepare her… Sharpless dares not tell her of Pinkerton’s marriage. Has he forgotten her? she lets out a shriek and exits. And brings in her son . ‘Is it his?’ – Has he seen a Japanese child with blue eyes. Opolais, movingly, would rather take her life than use him to beg for money.

Finally, Pinkerton’s ship is sighted. He has come back and loves her! Opolais stoops in ecstasy. Poignantly, she feels she’s aged with the waiting, and asks Suzuki for rouge.

Pinkerton returns. She’s been waiting all night with her child. Did he tell her; who is that in the garden? She is his wife, explains Sharpless to Suzuki. ‘The spirit of the ancestors come back for the little one’, Nakani’s Suzuki passionately defending her mistress. Sharpless knows they can offer Butterfly no comfort. And the lady’s to come into the house? – Better if she confronts it. Pinkerton sings, he’s filled with remorse. Sharpless warned him, he didn’t listen. Now Petri in his Adio, fioriti asil aria, admits his weakness and cowardice. He’ll never forget her. We might almost believe him.

Suzuki must talk to her alone, knowing Butterfly will weep (Nkani powerfully moving with Opolais.) That woman, what does she want of me! They want to take her child. Generously, Butterfly addresses Mrs Pinkerton, not to be sad on her account.

The denouement is indeed shocking. Cio-Cio-San coolly assesses the situation. She will give her child to her father and no one else. Alone she takes leave of her son (Opolais as if he were her own.) He must never know his Butterfly died for him. She goes behind a screen and we hear the knife drop.

Vienna’s is a ‘traditional’ Japanese production. But aren’t these Japanese cultural artefacts – timeless, the cultural ‘other’ against the onslaught of globalisation – just as relevant as in 1904? P.R. 14.09.2016

Photos: Kristine Opolais (Cio-Cio-San); Piero Petri (Pinkerton)

© Wiener Staatsoper/ Michael Poehn

Featured images reproduced from Wiener Staatsoper programme Puccini Madama Butterfly (1991) of posters from the Milan 1904 premier.

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog