Gloger’s production goes on a musical journey – a time travel spanning 400 years, leading back to the 18th century! Re-jigging the ‘historical’ narrative to push a ‘feminist’ agenda. Confused?

The stage curtain is a tapestry, with a spotlight homing-in on a cameo of Dubarry, blown-up, magnified – as Volksoper Orchestra play Millöcker’s Overture – putting the story into historical perspective.

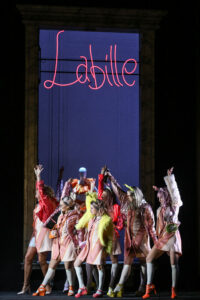

Yet Volksoper’s production opens- I kid you not- in a modern boutique, ‘Atelier Labille‘, letters in pink neon (stage Christof Hetzer). The shop girls dressing the windows, changing mannequins, Labille (Ulrike Steinsky) in black, glowering. Jeanne (Dasch) and the petite Margo (Juliette Khalil) complain of workers’ exploitation. Margot wants to be an actress, but is a target for older men, predators, stalking, abetted by Labille. One ‘admirer’ gropes her breasts. This is the producer’s agenda, ‘to position Dubarry in a perpetual, never-ending history of sexism.’ But the MeToo message – however important- is inappropriately heavy-handed (sorry!) for what is operetta.

Yet Volksoper’s production opens- I kid you not- in a modern boutique, ‘Atelier Labille‘, letters in pink neon (stage Christof Hetzer). The shop girls dressing the windows, changing mannequins, Labille (Ulrike Steinsky) in black, glowering. Jeanne (Dasch) and the petite Margo (Juliette Khalil) complain of workers’ exploitation. Margot wants to be an actress, but is a target for older men, predators, stalking, abetted by Labille. One ‘admirer’ gropes her breasts. This is the producer’s agenda, ‘to position Dubarry in a perpetual, never-ending history of sexism.’ But the MeToo message – however important- is inappropriately heavy-handed (sorry!) for what is operetta.

Musically, Millöcker re-mixed, somewhere late Roaring Twenties, brassy, jazzy. Annette Dasch’s Jeanne is a wonderfully rich soprano. In a show of ‘girl power’, the shop girls support each other; one even takes a group photo on her phone. We see Dasch working late, checking boxes, trying on a sweater. But she walks out, won’t take it anymore.

But the men, ‘nobility’ in the plot, carry on getting drunk. The elderly Marquis, pissed, shakily carries a beer glass. They’re slobs, whatever their titles, caricatures of sexists. They’re gross and gropers, as we see them in a party with girls on their laps.

Jeanne’s lover (Lucian Krasznec) an artist, is the only nice guy. Singing Frühling, Frühling, he’s a traditional tenor for operetta, generous, rhetorical, heart-on-his-sleeve, the old-fashioned crooner, singing of Die Liebe. Krasznec and Dasch’s scenes together are the operatic high-point in this production that’s short on musical highlights, too much of it spoken dialogue.

The scene changes to the struggling artist’s garret- grim; grey, grimy walls.  The bed is white, at least. They strip off their clothes, passionate, oblivious…Yes, Krasznec’s tenor is good, but old-fashioned, like the score, which could be a background to a black-and-white film noir. Who wouldn’t want to be out of this hole?

The bed is white, at least. They strip off their clothes, passionate, oblivious…Yes, Krasznec’s tenor is good, but old-fashioned, like the score, which could be a background to a black-and-white film noir. Who wouldn’t want to be out of this hole?

One of Jeanne’s ‘admirers’ comes ostensibly to look at René’s paintings. (He’s an acquaintance of Madame de Pompadour.) A mysterious Pompadour look-a-like floats across the stage, ballooned silks, the iconic built-up hair piece.

The aristocrat wearing a black fur coat must be suspect. He’s come intending to buy paintings; but she insists she’s ‘not for sale’.

There’s a moment of absolute silence- not a sound from the orchestra- as she makes up her mind. To consider Count Dubarry’s offer. She’s not given any time. (He throws some money, which René later finds, and hysterically accuses Jeanne of prostituting herself.)

At last a musical number! What looks like a speakeasy: a club with girls on men’s laps. And a ballet scene, with young men wearing appliqued hearts, dressed as cupids, carrying bows and arrows.

But the singer is Jeanne, Dasch in a slinky silver dress and wrought silver headpiece. Auf meine Welt. Is this creep on his knees offering her 50,000? A deep-voiced Marschallin (Ursula Stensky), coughing, chain-smokes cheroot.

Cherchez la femme, sing the men, all wearing black dee-jays. It’s so exaggeratedly sexist it’s embarrassing. These are ghouls out of a long-unopened closet. Gambling tables with men behaving badly. In a shocking MeToo moment, that balding, paunchy Marquis de Brissac (Wolfgang Gratschmaier) wrestles with Jeanne, pushes her to the floor, and tries to rape her. She’s rescued, the aristocrat’s face is bloodied. Dasch sings, I give my heart to only one man.

Cherchez la femme, sing the men, all wearing black dee-jays. It’s so exaggeratedly sexist it’s embarrassing. These are ghouls out of a long-unopened closet. Gambling tables with men behaving badly. In a shocking MeToo moment, that balding, paunchy Marquis de Brissac (Wolfgang Gratschmaier) wrestles with Jeanne, pushes her to the floor, and tries to rape her. She’s rescued, the aristocrat’s face is bloodied. Dasch sings, I give my heart to only one man.

Meanwhile Khahlil’s Margot, her friend wearing an exotic hat and other finery, has become a ‘heartless woman’. She’s seen checking out of the Atelier, her sugar-daddy buying outfits for her, loaded with designer carrier bags. While on the streets beggars hold up placards, Ich habe Hunger.

Opening Act 2, Jeanne is receiving a crash-course in social etiquette: the ways of the noblesse, (and here specifically the Austrian nobility). The significance of greeting people in the A-Z of 18th Century social manners. We are in Count Dubarry’s castle, and the entire second Act is in period costumes. The voice coach defers to the Count (Marco Di Sapia), wearing a white ‘smoking jacket’- the epitome ‘thin white Duke.’

A song! A waltz plays as servants pull on Jeanne’s corsets. Now she’s ready to be presented at her first ball. Schönheit, the duty of all beautiful women. Volksoper’s stage revolves to reveal all that’s going on in the palace.

Rene makes a surprise visit. He’s still in modern dress, wearing the same suit. They appear to make love- observed through a peep-hole by the Count. But she admits her fate (Schicksal) is sealed.

A state room in the Palace, an ‘historical room’ where Lous XV first met Madame de Pompadour. Louis XV is played by Harald Schmidt, a talk-show legend here in Austria. The scene turns into a roll-call of famous woman personalities. (All-very-witty if you can follow the dialect.) Now 30 years on the throne, it’s the first time he’s been in love: to the most charming, intelligent woman in France.

Cue, ‘Ich bin mein Herz’, one of the most memorable of Millöcker’s numbers. But generally the music (in Dubarry) seems vacuous. Maybe to do with (Volksoper conductor) Kai Tietje’s version?

A stylised court scene, beautifully lit (Alex Brok) to look like an 18th Century painting (Watteau?) come to life, is a highlight. Another is a rococo musical interlude with a flute solo (in the style of Telemann.)

A stylised court scene, beautifully lit (Alex Brok) to look like an 18th Century painting (Watteau?) come to life, is a highlight. Another is a rococo musical interlude with a flute solo (in the style of Telemann.)

But for all the seductive glamour, remember this is the Ancien Regime, pre-French Revolution- corrupt, degenerate, and repressing the masses, the peasantry. The people’s demand for Liberty, Equality and Fraternity exploded in 1789.

In one of the set pieces, servants dressed (realistically?) as sheep are goaded, submissively crawling under the tables.

In the Finale, Jeanne,(now Dubarry) declines René’s invitation to escape. Dubarry declares she’s a woman in love. With Louis XV- even if he weren’t King. Later, in an unsettling moment, she’s abducted. A plaque is held up reading that Dubarry died 1793 on the guillotine.

It has its moments. But Mackeben’s reworking of Millöcker’s score is problematic, Mackeben an artist working through the Nazi era. Too much of the music is overblown, kitsch of that period. And now the text/dialogue is inflated to include topical in-jokes and commentary. Yet Millöcker- once a rival to his contemporary Johann Strauss II- shines through. © PR 9.9.2022

Photos © Annette Dasch (Jeanne Beçu), Juliette Khalil (Margot), Ensemble; Annette Dasch, Lucian Krasznec (René); Annette Dasch, Marco di Sapia (Count Dubarry); Annette Dasch (Countess Dubarry), Harald Schmidt (Louis XV)