The bald devil-like figure of Josef Wagner storms onto the Vienna Volksoper stage threatening, there will be no performance tonight. This is a clever reference to the fires that broke out in opening performances in Vienna (1881) and in Paris at the Opéra Comique (1887), where the whole orchestral area was destroyed- the devil’s revenge for Offenbach’s satrical representation of hell in Orpheus in the Underworld.

The bald devil-like figure of Josef Wagner storms onto the Vienna Volksoper stage threatening, there will be no performance tonight. This is a clever reference to the fires that broke out in opening performances in Vienna (1881) and in Paris at the Opéra Comique (1887), where the whole orchestral area was destroyed- the devil’s revenge for Offenbach’s satrical representation of hell in Orpheus in the Underworld.

However, Renard Doucet and André Barbe’s production of Hoffmanns Erzählungen opens in Luther’s wine and beer cellar with a cheeky “Hell” sign. In the boozy atmosphere the Muse (classical inspiration for poets) is embodied in the genderless Niklaus (Elvira Soukop.) She urges Hoffmann, think of your writing, free yourself in art. He’s weak, she sings, but he responds to beauty and music.

Lindorf (Josef Wagner, whose impressive bass features as Coppelius, and Dr.Miracle, in the other tales,) is also in love with the singer Stella, and marks Hoffmann as a rival. Lindorf haunts the poet like an immovable adversary, as if to blame for all Hoffmann’s doomed love life.

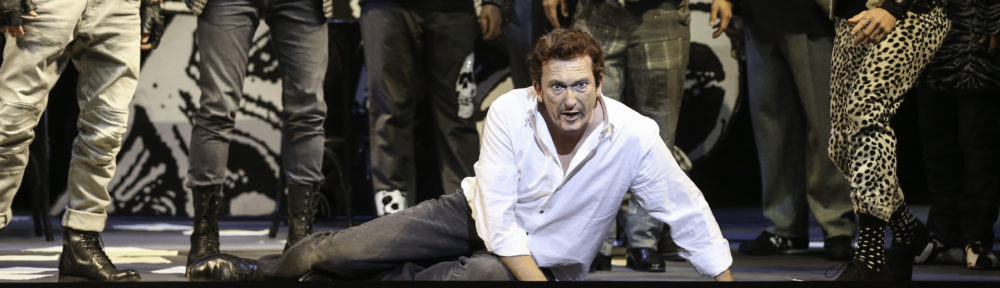

Much better is Act 2 in which a Frankenstein physicist has created a mechnical doll, Olympia , who he presents as his daughter. Hoffmann becomes obsessed with Olympia, and offered some magic glasses by Copelius (again Josef Wagner), imagines her . The stage is filled with weird half-human creations: a fantastical Hieoronymous Bosch tableau brought to life. Olympia is a clockwork cinderella , a pantomine dame with green hair and hooped skirt. But unexpectedly in Elisabeth Schwarz, she’s endowed with the most beautiful soprano, capable of astonishing runs of coloratura. The joke is that she moves , while her ‘legs’ are hanging over the huge canopy of her skirt. And she’s complemented by the wonderful tenor of Schwaninger. In spite of the kranky, curiously old-fashioned sets – surrealistic, gothic- the singing is wonderful. Schwaninger is outstanding as Hoffmann, a star tenor in the making, and Schwarz would grace any opera house.

In Act 3 Hoffmann is engaged to the singer Antonia (Cigdem Soyarslan), and opens with her aria Elle a fui , The dove is flown away. The set is like an ice palace , everything frozen , as if snow has drifted in onto the stage. Her father Krespel (Stefan Cerny), white-haired, is a ‘Phantom of the Opera’ figure, whose wife, a once famous opera singer, died of a mysterious illness.

They play her records on a wind-up gramophone. Note the opera box within the stage. Soyarslan, all in white satin and tiara, sings a gorgeous aria . She’s forbidden to sing – what may have have killed her mother; but on Hoffmann’s return, rapturously re-united, they sing of their love, C’est un chanson d’amour. Their love scene is in the French operatic tradition , but a little melodramatic: she feints with exhaustion.

They play her records on a wind-up gramophone. Note the opera box within the stage. Soyarslan, all in white satin and tiara, sings a gorgeous aria . She’s forbidden to sing – what may have have killed her mother; but on Hoffmann’s return, rapturously re-united, they sing of their love, C’est un chanson d’amour. Their love scene is in the French operatic tradition , but a little melodramatic: she feints with exhaustion.Hoffmann orders Antonia she must give up singing, to save her life, and her mother’s fate. What a terrible sacrifice! But the doctor, a vampyric figure, (Wagner again), maliciously conjures up the voice of her dead mother. She’s lured into singing again by a chorus waving their fluorescent strips, like wands. She’s spellbound; but when she falls – what a collapse- her fall looks painful. Their love song is played on a flute – excellent playing from Volksoper orchestra under Gerrit Priebnitz. Finally, the devil as doctor enters one of the Volksoper boxes- occupied with an elderly lady looking on in astonishment. What theatre!

We’ve had to wait until Act 4 for the Barcarole (‘Belle nuit’) but the wait was worth it. Behind a shimmering curtain, a cloudy scene as if under water. Out of an ornate gold-patterned, art nouveau portal emerge a can-can review which moves to the front of stage. They are minimally dressed, almost naked. Across the stage move sets of occupied plush red velvet chairs. (Are they meant to be gondolas?) In Hoffmann’s Chant Bachique – the song heard all over Venice- Schwaninger sings, Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour . But Hoffmann has lost faith in love, and sings in praise of pleasure and fun. Yet he’s passionate about Giulietta , Kristiane Kaiser, a cool platinum blond, as the courtesan, the third of his three loves.

In the preposterous plot Hoffmann , to prove his love for Giuletta, has to kill the jealous Schlemihl (yiddish for idiot), for her appartment key. But Giuletta hands over the reflections of her lovers to the scheming Captain Dapertutto (Wagner again). Wagner, a classy baritone, sings sublimely of Giuletta’s irresistible eyes. Shining diamond! And the spotlight hits the mirror of the portal, to dazzling effect.

In their duet, Giulietta demands Hoffmann’s reflection. She’ll make a toy of him, he counters: that a woman could make a pact with the devil! But she reassures him, ‘listen to love singing’, Kaiser a very competent soprano. Hoffmann, a soft touch, professes his love for her. Again tremendous singing from Schwaninger.

In their duet, Giulietta demands Hoffmann’s reflection. She’ll make a toy of him, he counters: that a woman could make a pact with the devil! But she reassures him, ‘listen to love singing’, Kaiser a very competent soprano. Hoffmann, a soft touch, professes his love for her. Again tremendous singing from Schwaninger.The plot gets very complicated in this ‘fantastical opera’ , but the main thing is the dazzling spectacle. The dancers move in gold behind the shimmering curtain, in Doucet’s stunning choreography.

She’ll follow wherever he goes; he’s drunk with glory. But Hoffmann, outraged, sings he’s been deceived, he a new victim of her perverse pleasures. In a rage , he stabs at her reflection. Mirrored glass shatters – a body falls, he and Niklaus escape – the glass re-formed in a geometric pattern.

In Act 5, ‘And so ends the last of my three loves’, the stage-set reverts to the symbolic giant skull and its clock parts. Offenbach worked seven years on the opera , but left it unfinished in 1880. ‘Hoffmann’ would kill him, he wrote. ‘The Tales are dreams, or nightmares: a journey into a composer’s unconscious, the attempt to find love and ultimately create a masterpiece.’

In the last Act , Hoffmann is drunk, too drunk, to speak to Stella, (who leaves with Lindorf.) He’s helped up by Niklaus’ Muse (Soukip) , whom Hoffmann embraces, (also metaphorically.) In the opera’s final tableau, the stage cast come together; his three past loves are sitting in the stage’s opera box. Behind the muse they sing, the greater the love the greater the pain: On est grand par l’amour et plus grand pas les pleurs. But tears of unhappy love are good for a writer’s soul, and they pick up pages of Hoffmann’s poetry strewn all over the stage.

Please note, although the libretto is in German, ‘to make sense and retain dramatic integrity’ many of the songs and musical ensembles are in French. Don’t let that put you off! Unaccountably, the sub-titles are in German, hardly welcoming to English speakers. PR. 3.11.2016

Photos: Kristiane Kaiser (singer) and Josef Wagner (Dapertutto); Wolfganf Schwaninger (Hoffmann) ; Josef Wagner (Dr. Miracle) and Cigdem Soyarslan); Kristiane Kaiser

(c) Wiener Volsoper/ Barbara Palffy