![Lohengrin_90507_VOGT_NYLUND[1] C](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Lohengrin_90507_VOGT_NYLUND1-e1467376686536-1024x958.jpg) If you were expecting – as I was- spectacular tournaments, knights in shining armour, then you’d be disappointed. Vienna State Opera’s set is a polished-oak hall, starkly puritan, reflecting German Protestantism. While the famous Prelude is being played the hall serves as a chapel, with a coffin laid out; then a wedding celebration interrupted, with chairs toppled. A trailer for the action, rather than the spiritual invocation of the Holy Grail. Vienna State Opera Orchestra play under the competent Graeme Jenkins. But onstage it’s State Opera’s Choirs that seem omnipresent, the men dressed in traditional green blazers, hats and shorts, similarly the women. Producer Wolfgang Gussmann is right to set the opera in the 19th century: the medieval narrative is seen through the prism of Wagner’s own time.

If you were expecting – as I was- spectacular tournaments, knights in shining armour, then you’d be disappointed. Vienna State Opera’s set is a polished-oak hall, starkly puritan, reflecting German Protestantism. While the famous Prelude is being played the hall serves as a chapel, with a coffin laid out; then a wedding celebration interrupted, with chairs toppled. A trailer for the action, rather than the spiritual invocation of the Holy Grail. Vienna State Opera Orchestra play under the competent Graeme Jenkins. But onstage it’s State Opera’s Choirs that seem omnipresent, the men dressed in traditional green blazers, hats and shorts, similarly the women. Producer Wolfgang Gussmann is right to set the opera in the 19th century: the medieval narrative is seen through the prism of Wagner’s own time.

Lohengrin attests to the 19th century interest in medieval chivalry, Arthurian legend, the Knights of the Holy Grail. In Wagner the mythology has a modern psychological dimension, in the heroine Elsa’s dream of her knight; later in her pre-wedding doubts, marrying a man she’s never been intimate with. Ostensibly the plot is about Elsa’s right to succeed her father, Duke of Brabant; her brother disappeared in Ortrude’s conspiracy.

Lohengrin attests to the 19th century interest in medieval chivalry, Arthurian legend, the Knights of the Holy Grail. In Wagner the mythology has a modern psychological dimension, in the heroine Elsa’s dream of her knight; later in her pre-wedding doubts, marrying a man she’s never been intimate with. Ostensibly the plot is about Elsa’s right to succeed her father, Duke of Brabant; her brother disappeared in Ortrude’s conspiracy.

In the opening, the King (Kwangchul Youn), intercedes in the dispute, with Telramund (Thomas Johannes Mayer) accusing Elsa (Camilla Nylund)- described as a ‘perpetual dreamer’- of murdering her brother: ‘robbed of his precious jewel, her terrible guilt for all to see.’

Nyland, in a white slip, her hair unadorned, enters looking bewildered. But instead of replying to the chorus assuming her guilt, she sings of her dream. She had prayed for her poor brother; and in her loneliness. As if in a religious revelation, a knight appeared, resplendent in armour and helmet, offering to defend her. He comforts her with friendly gestures. Nylund, in her simplicity, her powerful soprano clear, artless, is well-suited to this ‘angelic’ role.

By contrast, Telramund in Mayer’s excellent portrayal, the villain egged on by his scheming wife, protests his honour and reminds the King of his service; in medieval protocol, ‘God alone shall decide, through a trial by combat.’

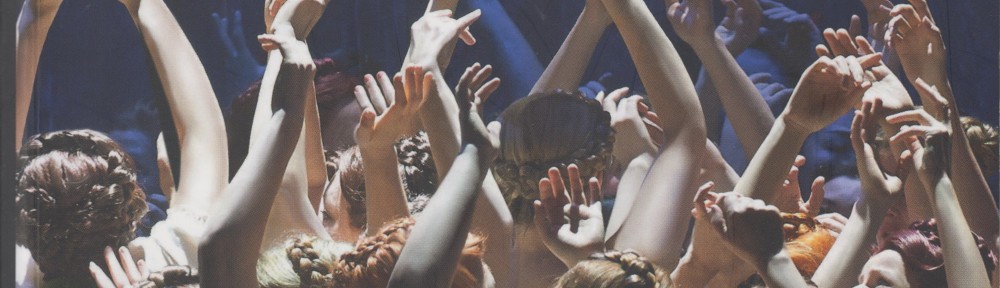

The ‘trial’ is like a spiritual revivalist meeting. Elsa calls upon her knight; Nyland stands immutable, as if possessed. ‘In this silence, God directs. See what a wonder’. She holds a white swan aloft; then they’re all holding their hands up, like in a prayer meeting. She seems to collapse exhausted. A figure in white toga-like robe, hidden by the crowd, emerges. Klaus Florian Vogt is blessed with a gloriously pure, dare I say ‘angelic’, tenor. ‘I shall give you all that I am’. He offers Elsa his protection and marriage, on condition of his anonymity.

The ‘unknown knight’ defeats Telramund in a wrestling match (on a raised platform)- Vogt in preppy green blazer, Mayer, bearded, wild-looking in white top and shorts- all over very quickly. ![Lohengrin_90501_SCHUSTER[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Lohengrin_90501_SCHUSTER1-150x150.jpg) Ortrud stands by, Michaela Schuster, red-haired, sensuous in maroon velvet.

Ortrud stands by, Michaela Schuster, red-haired, sensuous in maroon velvet.

If all this seems too sanctimonious, then Act 2 , with Ortrud like a Lady Macbeth goading her lily-livered husband, is full-blooded Wagner. The sloping stage, table upturned, simple as in a mountain lodge – could be Act II of Die Walkure . In fact, Schuster debuted here as Sieglinde in 2006,and has sung Waltraude and Fricke. Her magnificent soprano made my evening. Erhebe dich , she exhorts Telramund, rise up. Barred from the wedding celebration, her honour is lost. (Meine Ehre habe ich verloren.) And she had lied to him; said that she saw Elsa drown her brother. She, the last line of Brabant, had deceived Telramund into marrying her. Lied! –Entsetzlich! (dreadful). Will he threaten a woman, she thunders. As for the Knight, she, raised in the dark arts, will show him how weak his God is. (Her strategy to make Elsa doubt the Knight: thus extinguish his magic powers. Then Telramund could win back his honour.) They embrace, like the Macbeths, in complicity. Tremendously acted.

Bathed in a gold light, enters Elsa. (Nylund) sings she must tell the heavens of her joy; he’d journeyed through heaven for her. She’s observed by Ortrud. It’s the eternal battle between good and evil. Oh, but you are happy! She’d happily send her to her death . Ortrude sings, invoking desecrated gods, Entweihte Götter – Wodan god of strength, help her in her revenge. Schuster is exhilaratingly bloodthirsty.

Now Ortrud insinuates herself into Elsa’s trust. May he never leave you, as he came to you, by magic. Elsa counters, has she, Ortrud, never known the happiness that comes from trust?

The wedding day. Tables laid out, Nylund in white, ladies-in-waiting fitting her wedding dress, praising her chaste fervour, as Elsa’s walks to the altar. All disrupted! Ortrud disputes the legitimacy of the marriage; Elsa cannot give her husband’s name! Elsa is floored by Ortrud, Schuster in red, triumphantly commanding the proceedings, standing on top of the white-clothed wedding tables. But your husband, she rails at Elsa, who knows him? You cannot give his lineage, his nobility.

The knight arrives, hailed by King and courtiers as their saviour. But what secrets is he harbouring? Telramund accuses the knight of sorcery. Doubt is implanted in Elsa’s mind. But, ‘it would be ungrateful for her to question her saviour in public’, he urges. Vogt, who stepped in at short notice, could not have been bettered in the part. Long, blonde hair, bearded, radiantly handsome, but an innocent, his tenor still with a choir-boy’s purity. ‘Does the power of doubt not let you rest’, he asks of Elsa.

The sublime Prelude, leading into the Wedding March. Facing over separate tables, they’re alone for the first time; no one can hear the secrets of their hearts, he sings. He ‘breathes with an ecstasy only God could give him’. He draws close to her. Elsa, meine Welt.’ – ‘Will you not let me hear the sweet sound of yours?’ Now they’re alone, she wishes to know his secret, where he came from.

![Lohengrin_90514_VOGT_NYLUND[1]](https://viennaoperareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Lohengrin_90514_VOGT_NYLUND1-e1467377257689-150x150.jpg) His response is almost arrogant. He’s already placed his utmost confidence in her; he will esteem her above other women if she has total confidence in him. Her unfaltering love is his expected reward. (In Wagner’s world, 19th century patriarchy demands woman’s unquestioning submission.) He sings, he comes from a place of radiance and joy. But she’s filled with sadness: how can her love suffice for him if he’s to return to this heaven. Her anxiety is to keep him here.

His response is almost arrogant. He’s already placed his utmost confidence in her; he will esteem her above other women if she has total confidence in him. Her unfaltering love is his expected reward. (In Wagner’s world, 19th century patriarchy demands woman’s unquestioning submission.) He sings, he comes from a place of radiance and joy. But she’s filled with sadness: how can her love suffice for him if he’s to return to this heaven. Her anxiety is to keep him here.

We see Telramund sneaking in and hiding. Vogt slays the intruder: ‘Now all happiness is lost.’ Vogt, distraught, orders Telramund’s nobles take the corpse to the King.

King Heinrich is hosting tables lined with white-shirted regiments. ‘German swords shall protect German soil: we shall prove the might of our empire,’ they sing lustily. (Uncomfortable resonances.)

Chorus sing of the virtuous Elsa, how sad and pale she looks; of the hero of Brabant, they welcomed; his wife misled him into betraying himself, her solemn promise broken. Now he will reveal his name.

Vogt stoops, sings of a vessel, in a distant land, served by angels and priests, called the Grail; the heavenly power bestowed on its worshippers, sent to distant lands; he, sent by the grace of his father, Parsifal. ‘I am its knight, I am Lohengrin.’ How he longed to experience a year of happiness by her side! (We might, in another world- our 21st century- expect this alien to take off in his space ship.)

Elsa, of course, feels wretched that he must return. Ortrude had transformed Elsa’s brother into a swan. Now Lohengrin breaks the spell. A pale boy, in a foetal position- like an extra-terrestrial- crawls backwards centre-stage.

After nearly five hours, Wagner’s spell has suspended any disbelief- as a sci-fi epic transfixes a multiplex audience. Gussmann’s production, (dramaturgy Werner Hinzle), however, hints at a 19th century evangelical service. The ‘sequel’ is Parsifal, but I’d rather The Ring’s pagan gods of Valhalla. PR. 10.05.2016

Photos: Featured image, Wiener Staatsoper Ballet Academy (cover photo Wiener Staatsoper programme; Michaele Schuster (Ortrud); Klaus Florian Vogt (Lohengrin) and Camilla Nylund (Elsa of Brabant)

(c) Wiener Staatsoper/ Michael Pöhn

viennaoperareview.com

Vienna's English opera blog